In the end, they knocked out the door of the stall and caught me on the window sill.

Stáhnout obrázek

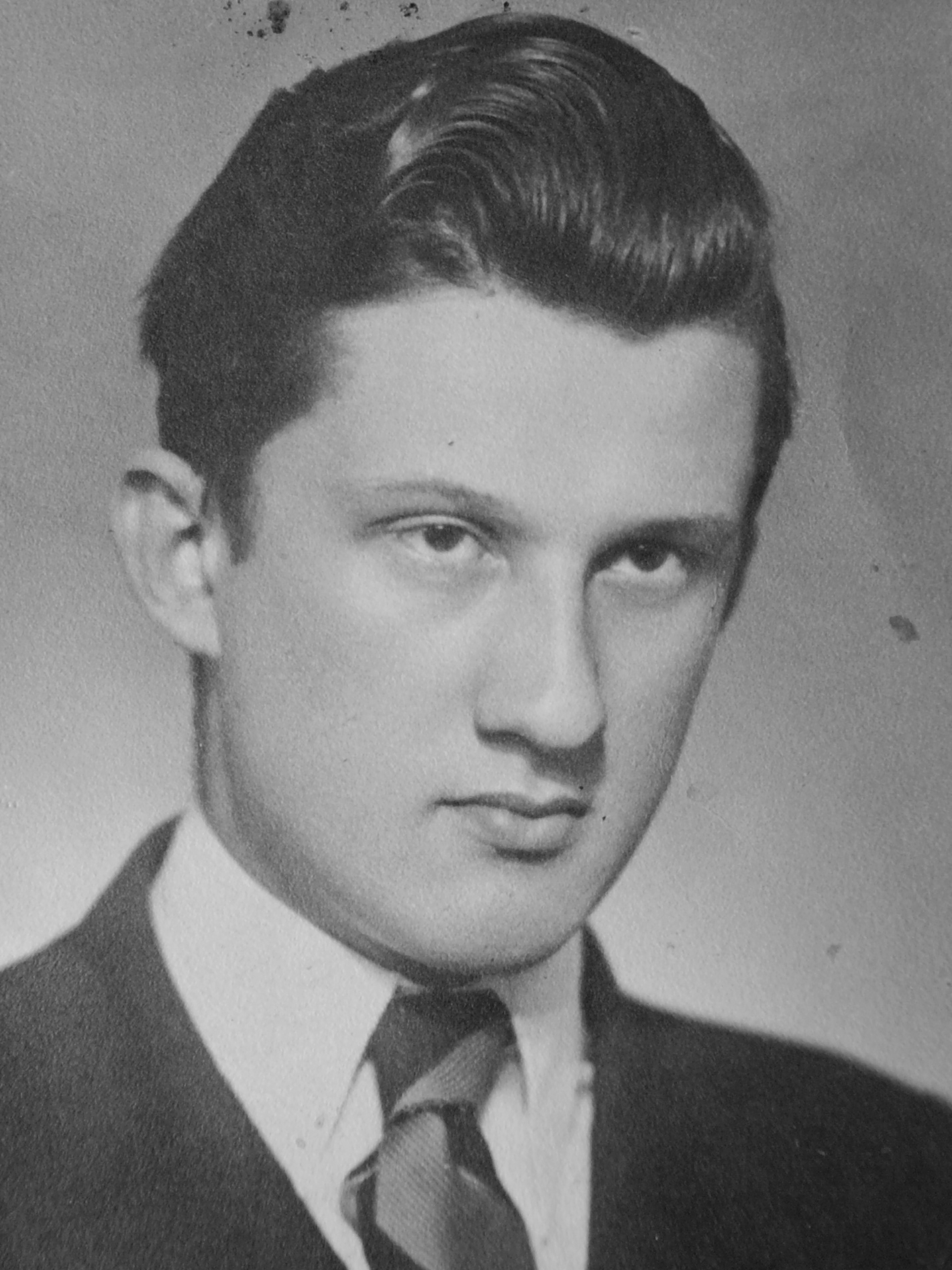

Jan Roman was born on March 7th, in 1929 in Carpathian Ruthenia. At the beginning of the war he moved to Moravia with his parents. After February of 1948, he began issuing anti-communist fliers with other students at his high school. In 1949 he was detained and convicted to 12 years of imprisonment. On October 28th, in 1952 he managed to escape from the Valdice prison. He hung around various friends and relatives, breaking into recreational cabins, until he decided to seek help at the parsonage -- a church owned house. While still in Valdice, he befriended the pastor Josef Kůnický who had been announcing in prison that the political prisoners would find asylum with him. Unfortunately, the local pastors at the parsonage reached an agreement that this could be riskt and amount to a provocation and refused to accommodate Roman. It seemed that they had reported the ‚alien person‘. He was arrested and escorted by train to Brno. During the journey he attempted another escape, though unsuccessfully. He asked his guard to let him go to the toilet -- he closed the door quickly and locked himself in. The policeman together with the other passengers knocked the door of the toilet out and caught Roman just as he was trying to climb out of the window sill. The interrogators thought that he was a thief who was robbing the cabins. Roman was convicted only to one year of imprisonment. After the death of Stalin and Gottwald he was to be released during the amnesty of criminal prisoners; the jury, however, uncovered his true identity and he was sent to the Jáchymov camp. He was released, (most probably due to a similar administrative error, in any case, as the last member of the original group) in 1955.