They wanted to release me, but Mum said no

Stáhnout obrázek

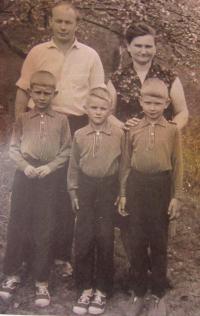

Helena Kociánová, née Maxiánová, was born on 20 November 1933 in Borský Svätý Jura in Slovakia. She experienced many difficult moments in her life. When she was eighteen she was arrested by the Slovak State Security. She suffered violent interrogations and ended up in a military hospital. Upon returning to prison, her freshly operated wound caught an infection and she was wracked with unbearable pain. In October 1952 she was sentenced to five years in prison during the trial with Krutý and co. And yet Helena Kociánová had not been doing anything seditious, she had merely advised a friend how to get in touch with a border guide, who could help him cross the border. On 12 June 1955 in the corrective labour camp Želiezovce, she was part of an incident that marked her for the rest of her life. While working with a rapeseed thresher the hood came loose and Helena Kociánová fell inside the machine. The thresher injured her severely and she had to have her leg amputated. After the operation, she was not given anaesthetics and she thus suffered great pains. Her leg did not heal and Helena Kociánová had to undergo several further operations and remain in hospital for almost a year. When her brothers visited her, she found out that she was supposed to have been released on probation the day after her accident, but that did not happen. Her release was later refused by her mother, so that she would not have to look after her invalid daughter. Helena Kociánová was not released until 1956. In the same year she moved away to Mikulovice in the Jeseník District, and ignoring her mother‘s disapproval, she married Karel Kocián. Influenced by his wife‘s bitter experience, her husband quit the Communist party in the early 1960s. She became a widow in 1986. In 1997 the Kociáns‘ house was severely damaged in a flash flood: it demolished half the house and destroyed the barn and garden. The house was repaired with the help of family and friends, and the witness lives there to this day.