Although all my family and I experienced really a lot, I cannot say that I would feel any strong hatred towards the former enemy – the Germans First, our religion says we should be merciful to others Secondly, it was not on the whole the fault of the people because they were commanded by someone, they were given commands by someone Perhaps if their state apparatus were different, then the disaster didn‘t have to happen

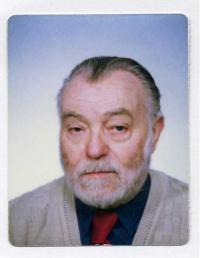

Miroslav Škrabal was born in a family of a carpenter and a seamstress in the Polish Rovno on March 17th, 1927. His Grandfather was a veteran of the Czechoslovak Legions in WWI. The family spent the Soviet occupation without any harm. However, some of its members died in bombing at the beginning of the German occupation. He witnessed the brutal treating the Jews by the German occupants as well as the harsh ethnic attacks of the Ukrainian semi-military gangs (especially the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) on the Poles and the Jews. He joined the Czechoslovak Brigade as a hardly-seventeen-year-old boy at the beginning of 1944. He started his training at the troop of Tank Unit. He was redeployed to signalmen at the Tank Brigade. He took part in many tough battles with the Czechoslovak Tankists (battles at the village of Machnówka, Wrocanka and Bóbrk, the battle of Gýrova Mountain, the tank battle of the ‘Nameless quota‘, the battles at Jaslo, Ostrava operation). He lived in Encovany for some time after the war, then he moved to Litoměřice. Miroslav Škrabal passed away on March, the 3rd, 2016.