Eduard Picka

* 1923 †︎ 2012

-

"The driver had a malfunction at the base of the hill, and the vehicle was immobilised. To which the commander, at the time that was Major Sacher, pointed out the malfunction and decided that we should carry on by foot and the driver should catch up later. We moved up some two hundred metres, on to high ground. It was a very strange situation all in all, deathly silence to the left and right, no one in sight, no soldier. The commander took out his binoculars, I noted that there were two soldiers moving along a dirt road close by, which when he found out, he was horrified. He discovered that they were Germans, and at the same moment we were under fire, so we started falling back. And we found out that we were in the no-man's land between the first trench line of the Germans and the first trench line of the Soviets. So that was one escapade. And if it hadn't been for the fact that the driver managed to get the vehicle started, we might have ended there."

-

"Well, all of our efforts were aimed at achieving success. And when the fighting in Dukla Pass itself proved to be so complicated and with so many sacrifices and such misfortune, it tormented all of us. That's also why the morale was in a dubious state and optimism was at a low. But we still believed that it would work out and that we would succeed. They way the Soviet army or the Red Army did it at the time was to withdraw the front-line units that were tired by the drawn-out combat, they replaced them, let them rest a while, replenish their numbers, recuperate... They offered that to Svoboda as well. Svoboda refused. Because we had reached our own land, that was the argument that he used. We agreed, although secretly we thought that a rest would do us no harm. But it was a matter of morality - we had reached our own land, the first of our villages, and it would've been immoral for us to have been withdrawn to the second line to rest."

-

"Well, in closing I'd like to say one thing about the Dukla Operation, I'd like to recall the words of the 3rd brigade's artillery commander. He always said, that despite what historians will claim of the Dukla Operation to either extent, it will remain a living memento for both our nations of those, who were willing to risk their lives for the liberation of their country even in extremely difficult conditions."

-

"It was always about one battalion of some three or four hundred boys say from the district where I lived in Kiev, each night, one battalion after the other. And I know that many times we met up with another such unit. There really was a very strict discipline enforced, blackout enforced during the night, as breaks of discipline attracted German bombardment and attacks along the fall-back lines."

-

"The layer of frozen ground varied according to the weather and stretched down to as much as sixty or seventy centimetres. So we had to drill that and blast it with explosives. The frozen ground would crack, that was the only way to make it reachable. We pushed that away and of course we had to dig down into the warm layer straight away, so that it wouldn't freeze up as well. We had to dig down night or day no matter the weather, had to keep digging. After completing the pit we had to see to the bunk beds, or whatever the technical term is, I dunno. And there was a problem with roofing, as their wasn't any hard material, it was hard to get, so we just used canvas, tent sheets. We were happy when they brought in any materials, some logs so that we could insulate and cover the dug-out up. When we got that done, we had trouble with heating. We had a small camp stove, but nothing to put in it. So we collected dry grass and used that for heating. One screamed to stop it immediately, that it was impossible to breath, another wanted to keep on heating as he was cold."

-

Celé nahrávky

-

Hradec Králové?, 23.01.2003

(audio)

délka: 02:02:16

Celé nahrávky jsou k dispozici pouze pro přihlášené uživatele.

„Our generation was out of luck. We had to struggle through World War II, and the post-war period wasn‘t exactly a piece of cake either.“

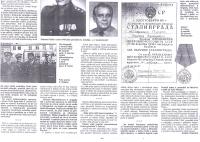

Eduard Picka was born in Pilsen in 1923. As a child, he left to join his father who had moved to the Soviet Union in search of work. After WWII broke out, he was evacuated along with other young men to Kiev in the East and was drafted into the Red Army in 1942. He took part in the Battle of Stalingrad. In 1944, he joined the Czechoslovak army, fought at Dukla and was part of the push through Branisko, Liptovský Mikuláš, Malá Fatra, Fryšták, Pivín u Prostějova. He remained in the Army even after the war. He studied at a topography school and artillery training center. After serving in various crews, he went into retirement in 1978. Eduard Picka passed away on January, the 29th, 2012