Ordinary human decency is enough

Stáhnout obrázek

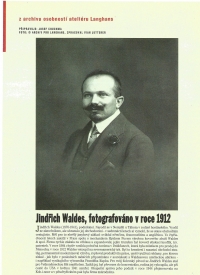

Jiřina Nováková, née Hromádková, was born on December 31, 1945 in Prague. She had a number of important ancestors in the family who helped shape the history of this country. Sigmund, the witness‘s grandfather, and his brother Jindřich Waldes were among the leading Czech businessmen. With diligence and discipline, they have developed from modest circumstances to the point where they have built up huge assets in Europe and beyond. In 1902, they opened the Prague factory for the production of haberdashery metal goods Koh-i-noor in Vršovice and based their success on the innovation of the production of patents. In addition, Henry was a generous patron and art collector, and at the same time caring about the education of his workers. Věra Waldesová, the witness‘s mother, was left-wing from her youth. During World War II, she became actively involved in the French resistance movement. At that time, she met Otakar Hromádek, the witness‘s father. After years of fighting in France against Franco, he was also active in the French resistance movement. The husband and wife Hromadkovi returned to Prague after the war in July 1945. The witness‘s father was a high-ranking party official, convicted in political trials in the 1950s and rehabilitated in the 1960s. In 1968, Hromádek emigrated to Switzerland, Jiřina stayed in Prague, graduated from the Faculty of Science and was allowed to see her parents after eleven years (a sister of seven). The influence of family upbringing is evident in Jiřina, she has always been and still is a brave person with an interest in public affairs. Since 1994, Jiřina Nováková has been trying to get back the family property built by the Waldes in Bohemia. The gruelling trial lasted 17 years and ended in a sad outcome. The former glory of the huge expansion of talent and diligence of the Czech Jewish family is lost. From 1996 to 2007, she was a witness in the broader leadership of the Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA) political party