May people finally realize that those were not only shackles on many men and women, but also on our nation; its fate and its story has been cruelly manacled.

Stáhnout obrázek

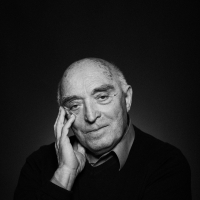

Rudolf Dobiáš was born to a peasant family on September 29, 1934 in Dobrá, near Trenčín. He attended public school in his hometown and then a grammar school in Trenčin from 1945 to1953. In his youth he was a boy scout, and eventually became the leader of a group in Trenčianska Teplá. After the ban of scouting, his squad began to illegally issue prohibited leaflets. As a student fresh out of University, he was arrested, accused of anti-state activity and high treason, and sentenced to eighteen years of imprisonment. He spent seven years in the correctional institutions, in labour camps in Jáchymov, Slavkov, and Příbram. In May 1960 he was released from custody and forced to enlist. After serving, he was employed as a temporary worker in mines, later as a workman and a technician in Slovlik Trenčín Enterprise. After years of odd jobs, he extended his education and completed secondary studies at the Industrial School of Chemistry in Bratislava. He started to become interested in both literature and theater while at school. In 1975 he received an award for a collection of short stories called Veľké biele vtáky (Big White Birds) and since 1976 he worked as a professional writer. From 1990 to 1992 he worked as an editor of Slovak Daily. He continued to publish his own work, including a series of writings called Triedni Nepriatelia I., II. (Class Enemies I. and II.), which deals with the fates of individuals being affected by the former communist regime.