Colonel Urban Ocilka

* 1919 †︎ 2008

-

„The Slovak reservists refused to fight against the Soviet Union. In one garrison they didn’t obey the order – it was a kind of a smaller rebellion. So they got punished and we – the basic service soldiers - were sent instead of them. They sent a train from Bratislava and basic service soldiers from each garrison got on. Before we reached Medzilaborce which had the last stop the train was already crowded. Then we crossed the border to Poland.”

-

„There was a tough river-crossing – the river was deep with high shores and rocks and it was impossible to put a pontoon there. The infantry crossed the river and attacked. But the artillerists couldn’t cross the river. The Germans routed our artillery. We set up the cannons on the other side of the river. All of a sudden I saw a tank approaching us. We fired at it but the first shot was too short. The second shot was too long again. I grew tired of it. Only the third shot hit the tank. But there was already another tank approaching our left flank. The tank stopped and the crew climbed out. We started to shell them with grenades. We destroyed the second tank as well. It was a great success – we destroyed two German tanks. The whole crew of our cannon was decorated.”

-

„I became a rheumatic from it. I was treated in a hospital in Rožumberok. From there I got back to the school in Liptovský Mikuláš. The doctor told me: “You need to undergo treatment, I’ll send you to the spa in Piešťany.” So I went to Piešťany. By that time the Germans attacked the Soviet Union. In the spa we listened to the radio and learned that the German armies were 192 divisions strong and that the attack was divided into several directions: One group was north-bound heading to Leningrad, the central group headed to Moscow and the southern group marched to Rostov. As we were sitting around that radio set I said that I was persuaded that the Germans are going to loose the war with Russia. Then I got afraid, however, because there was among us one German Slovak who came from the garrison in Rožumberok. I told him that one professor from Vienna wrote a newspaper article in which he claimed that the Germans were proceeding like a blind elephant and that they would throw themselves into catastrophe and that Germany would be divided into four parts. This German couldn’t stand me – he threatened to report me to the chief for subverting the moral of the troop.”

-

“What was your hardest assignment on the Czechoslovak territory?”

„Dukla! The fiercest fighting took place at Dukla. The Germans hanged on there. They wouldn’t let us through that pass because they knew very well that as soon as we pass we would drive them out of Slovakia. They apportioned further army units. There were so many casualties in the Dukla battles! The Soviets lost 80 thousand men there, the Germans 52 thousand Němci and the Czechoslovak army corps 6,500 men. All in all, Dukla cost 138 000 human lives. The price for Dukla was very high indeed.”

-

„My mother and I were against the Slovak state. The more states separate, the worse. I personally was for the Czechoslovak Republic. We were against the Germans already by the time they annexed the Sudetenland. I always knew that if I get into the army and they send me to fight against the Soviet Union, I’ll run away. And I did it and got to the Czechoslovak army.”

-

„We transferred to Jaslo on November 19, 1944. We showed them a perfectly prepared and coordinated attack. Under the cover of the night we occupied our firing positions, dug the trenches, brought in ammunition etc. On January 15, 1945 we started a massive offensive on a huge strip of the battlefront. The Germans got a monumental beating there and our artillery unit was part of this. We participated in a glorious victory! I was so proud that everything worked out so well for us.”

-

Celé nahrávky

-

?, 27.06.2004

(audio)

délka: 01:03:56

Celé nahrávky jsou k dispozici pouze pro přihlášené uživatele.

„I always knew that if I get into the army and they send me to fight against the Soviet Union, I’ll run away. And I did it and got to the Czechoslovak army.”

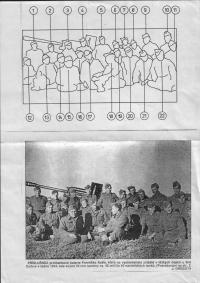

Urban Ocilka was born on May 25, 1919 in the village of Krábská in the district of Vránov nad Toplou in eastern Slovakia. Until he was twenty one he worked at the family mansion. His father died in and since then he lived with his mother. When the Slovak state came into existence he had to leave the mansion and in October 1940 join the Slovak army in Dolního Kubína. No one from the family acquiesced with the break up of Czechoslovakia. In 1941 he was sent to an officer school in Liptovský Mikuláš. The hard training caused Mr. Ocilka health problems that he has to cope with until today. Because of rheumatism he had to stay several weeks in the spa resort Piešťany. Afterwards he was supposed to return to the officer school, which, however, ceded to exist after the call for mobilization. Mr. Ocilka was sent to Poland where he was assigned to a field hospital and later to a field bakery. The hospital got as far as northern Caucasus.

On the eve of 1942/1943 the Battle for Stalingrad took place. Mr. Ocilka let himself to be captured by the Soviet army and after a month spent in the political camp Krasnohorsk he was able to join the Czechoslovak army. Due to his previous health problems Mr. Ocilka was assigned to the artillery. After training, his unit was deployed in Ukraine on the Dniepr River and later at Kyiv, where a counteroffensive was being prepared to liberate the city. He was also engaged in combat operations south of Fastov during Christmas-time 1943 and the hard battles for Bíla Cerekev.

Mr. Ocilka also fought at Dukla Mountain Pass and at Jasla. He later worked at the Ministry of the National Defense in Košice as head of the guard. After the war, Mr. Ocilka achieved higher military education at the War Academy in Hranice na Moravě. Urban Ocilek passed away on December 2008.