Thanks to the Charter 77, I was liberated internally

Stáhnout obrázek

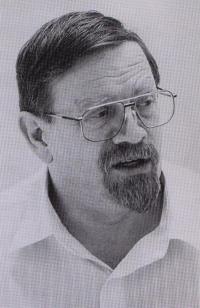

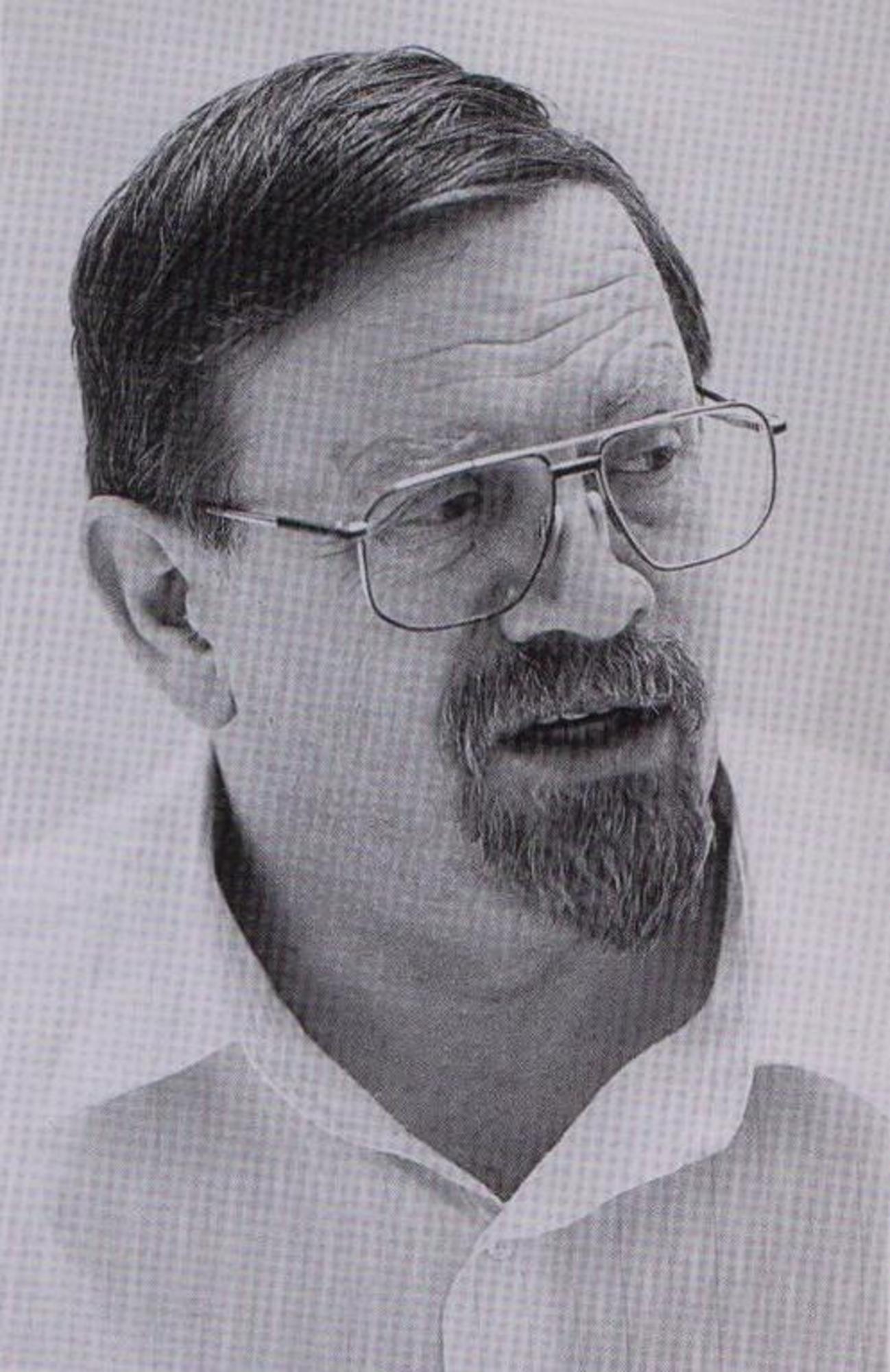

Mr. Daniel Kroupa was born on January 6th 1949 in Prague. His father’s moving company had been nationalized by communism right after February of 1948. The only reason he didn’t ended up going to jail for his wealth, was that one of his friends paid the ridiculously obscene „millionaire tax“ for him. Mr. Kroupa recognized his bourgeois origin during his grammar school years. During the school‘s Pioneer organization ceremony, where two hundred kids gathered, he was the only one who wasn’t given the red scarf - one of the Pioneer symbols. He discovered gradually that there is another world out there, besides for the one he’d been taught at school. For instance, when he once asked his father what Free Europe was (he heard that at home all the time), he didn’t get any answer. Instead he was forced to repeat three times:´Free Europe is a radio station, which my family will never listen to.´ The Free Europe radio station was on also in the Radio club of Svazarm organization, where he began to spent his free time when he was fourteen. The radio amateur operators knew how to get around the state‘s signal blocking; therefore Svazarm was the first place where Daniel heard the open criticism of the government for the first time. His technical interests from the radio club led him to the local Technical College, where he was admitted despite his family origin. In the same time, he started to attend the lectures at the Prague city library, where he met the translator and poet Mr. Jan Vladislav. This was also where he heard Mr. Jan Patočka speaking for the first time. After the August of 1968 revolution he was forced to work in manual labor. He dug up coal cuttings, to bring coal to elderly people, and sometimes he starred as an extra in the club‘s films. He continued visiting the lectures of Mr. Patočka and Mr. Černý, and thanks to his relationship with the Catholic community he also met young people from the Vigilie catholic organization. He continued to attend a few other similar organizations where he met people like Radim Palouš, Tomáš Halík, Zdeněk Neubauer, Pavel Bratinka or Ivan Havel. Daniel never finished his college studies though. He found himself a job with a cleaning company and he applied for external Faculty of Philosophy studies. He was dismissed from the school after he didn’t pass the exams regarding Marxism-Leninism. Following his signing of the ‚77 Charter in January of 1977, he was questioned by StB permanently since. He continued to be arrested during several anniversaries until the 80´s. But most of those times he usually left the town with his family. After the death of Jan Patočka in 1977 Daniel Kroupa decided to follow his foot steps and to continue in spreading the free mind which wasn’t dependent on the communist regime among the young people. He established his own philosophy seminar, which welcomed about fifty people through the November of 1989.In 1989 he was one the leaders of the newly established ODA political party. As the representative of the Federal Assembly of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic he participated on preparations of the Constitution of the Czech Republic. Mr. Kroupa was elected as a member of the Parliament of the Czech Republic and since 1998 he worked also in the Senate of the Czech Republic, until 2004.