Underground is a longing for freedom; not just long hair and a beard

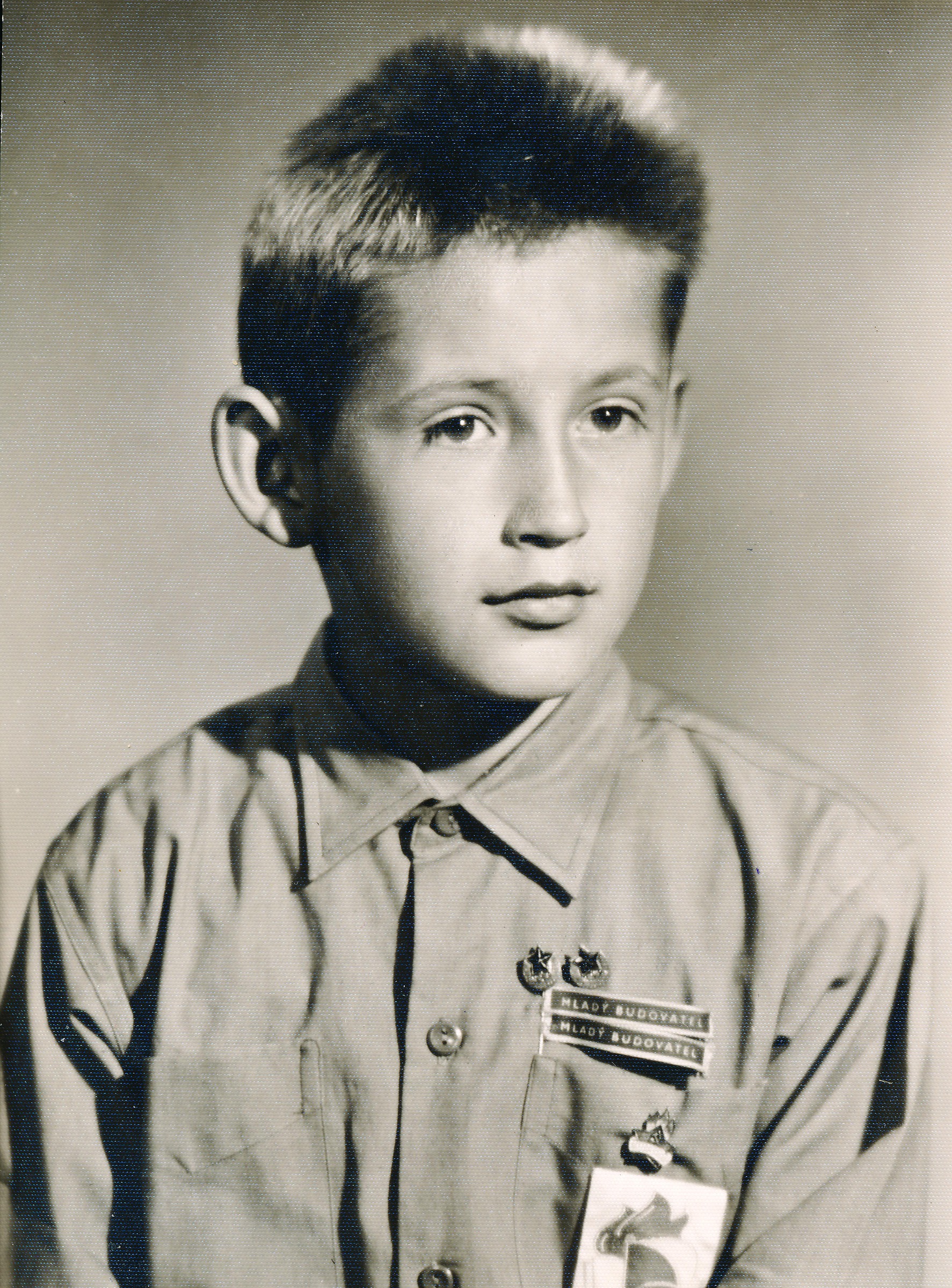

Karel Havelka was born on 12 July 1950 in Planá u Mariánských Lázní in the family of a carpenter and a teacher. Since mid-1960s, he was interested in beat and rock, through which he got to know the unofficial cultural scene. He started to organize concerts and lectures and take part in other underground events. During a trip to Japan in April 1973, he decided to emigrate and asked for political asylum in the US. He spent a year in Jersey City as a blue collar worker. In April 1974, he returned to Czechoslovakia because of his fiancé Věra. During his stay in the US, he was sentenced in absentia but granted parole because of his voluntary return. In February 1976, he was arrested and charged with disturbance for organizing a concert and a lecture. In the following trial against the band The Plastic People of the Universe, he was sentenced to 15 months in jail. He served his sentence in the Plzeň-Bory prison. Following his release in the summer of 1977, he signed the Charter 77 and continued to be actively involved in the unofficial cultural scene. He was repeatedly detained and interrogated. In September 1980, under the threat of being charged with espionage, he requested emigration. In the beginning of November 1980, he left with his wife and two small children for Vienna. As an exile to Austria, he distributed and sold exile literature and organized protests in support of Czechoslovak prisoners of conscience. He made a living by selling and later producing LPs. In 1990, he returned back to Czechoslovakia where we founded the music publishing company Globus International, which he was in charge of until 2002. At present, he makes a living importing wine and music media.