You judge me only because I am Ukrainian

Stáhnout obrázek

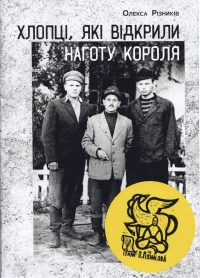

Oleksa Riznykiv was born on February 24, 1937, in the city of Yenakiieve, Donetsk region. After obtaining a qualification as a theater lighting technician, he worked in the theater in Kirovohrad (now Kropyvnytskyi). On November 7–8, 1958, together with his friend, the poet Volodymyr Barsukivskyi, they distributed anti-Soviet leaflets in Kirovohrad and Odesa. He was arrested on October 1, 1959, during his military service. He spent a year and a half in a camp for political prisoners in Mordovia. In 1962, he became a student at the Department of Philology of Odesa University. He worked for the newspaper Odeskyi Politekhnik and at the editorial office of the city TV studio, from which he was dismissed at the behest of the KGB. On October 11, 1971, he was imprisoned a second time. He spent five and a half years in the Perm-36 labor camp alongside other Ukrainian dissidents — Levko Lukyanenko, Yevhen Sverstyuk, Taras Melnychuk, and Dmytro Hrynkiv. After his release in 1977, he was forced to return to Pervomaisk due to pressure from the KGB. He worked as an electrician in a maternity hospital, then as an educator in a special-needs school for children with intellectual disabilities. His first poetry collection, Ozon, was published only in 1990, the same year Oleksa Riznykiv was accepted into the Union of Writers of Ukraine. In 1992, during a visit of former political prisoners to Israel, Oleksa met with dissident Arye Vudka, who had transported Riznykiv‘s poems abroad during his imprisonment in the 1970s. He is currently the editor of Zona, the journal of the All-Ukrainian Association of Political Prisoners, and is compiling a dictionary of syllables of the Ukrainian language.