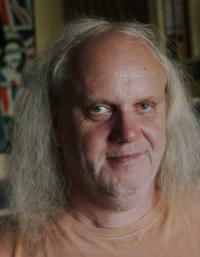

We didn’t want to fight the system, we just wanted to play the music we liked

Stáhnout obrázek

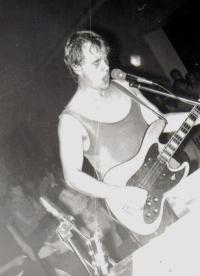

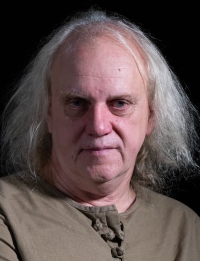

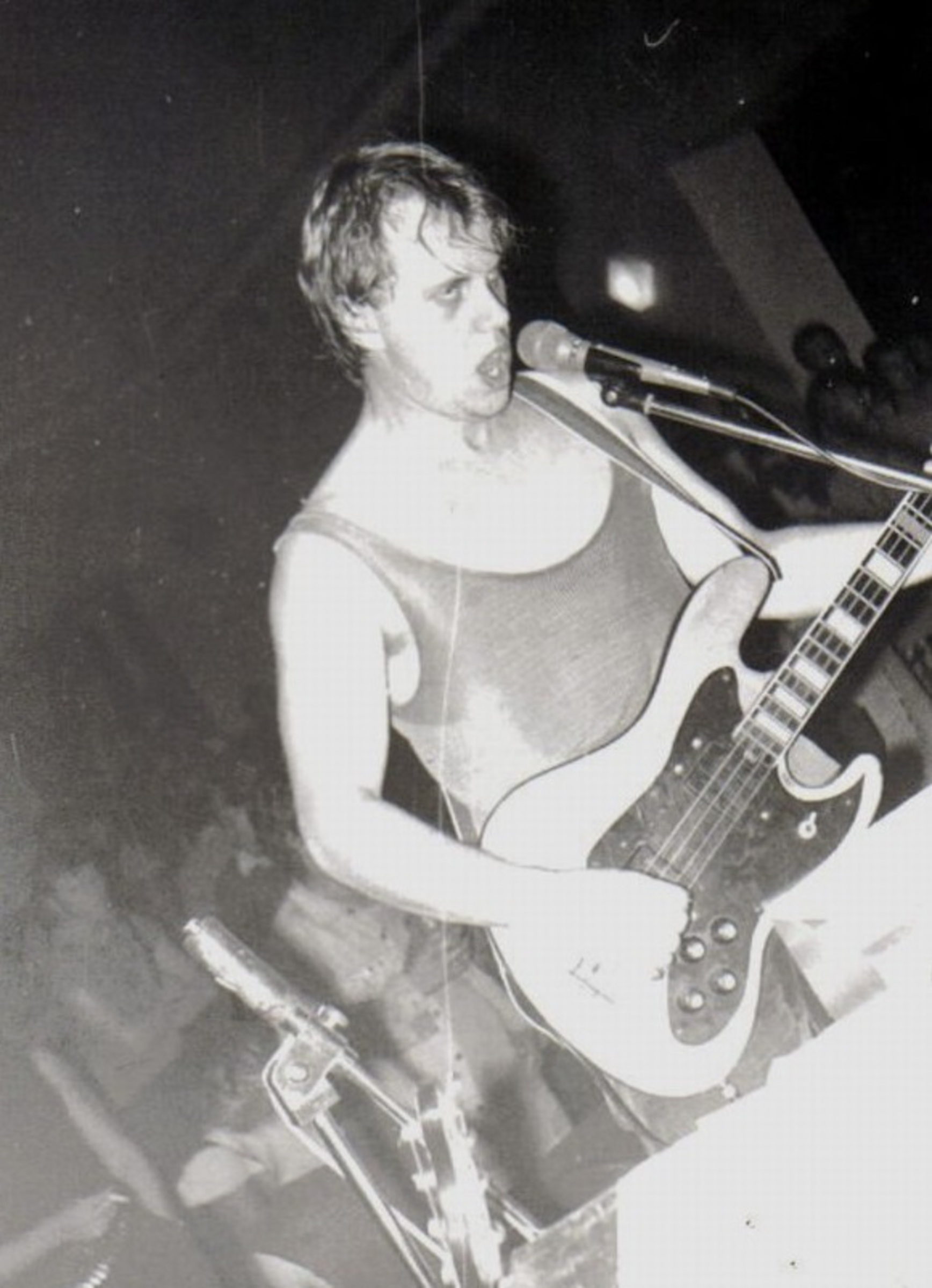

Miroslav Wanek was born on 6 April 1962 in teplice. He grew up in Dubí near Teplice, without his father and from when he was 9 also without his mother, who died tragically due to a work accident at the glass works. From then on he was raised by his grandparents. During a visit to Yugoslavia, enthused by a concert of the rock group Bijelo dugme, he decided to start his own band. He trained as a glassmaker in Nový Bor, where he became acquainted with the unofficial, „underground“ culture. In 1981 he established one of the first punk groups in Czechoslovakia, named FPB. Their very first concert earned them the attention of State Security. He also took an interest in literature in a writers‘ club, which officially published unofficial poetry collections and samizdats for two years. He was a member of the Pataphysical Collegium, which was led by Eduard Vacek. In 1985 he joined the band Už jsme doma (We‘re Home Now), which he plays with to this day. In 1989 he acted as the spokesman of the Civic Forum in Teplice. After the revolution - besides performing at concerts and recording albums - he composed the music to several films, published the poetry collection Máj (May), and taught at Tomáš Baťa University in Zlín and at the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague.