If that‘s your home, just go back there. But never regret it

Stáhnout obrázek

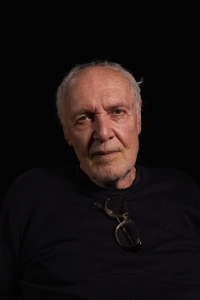

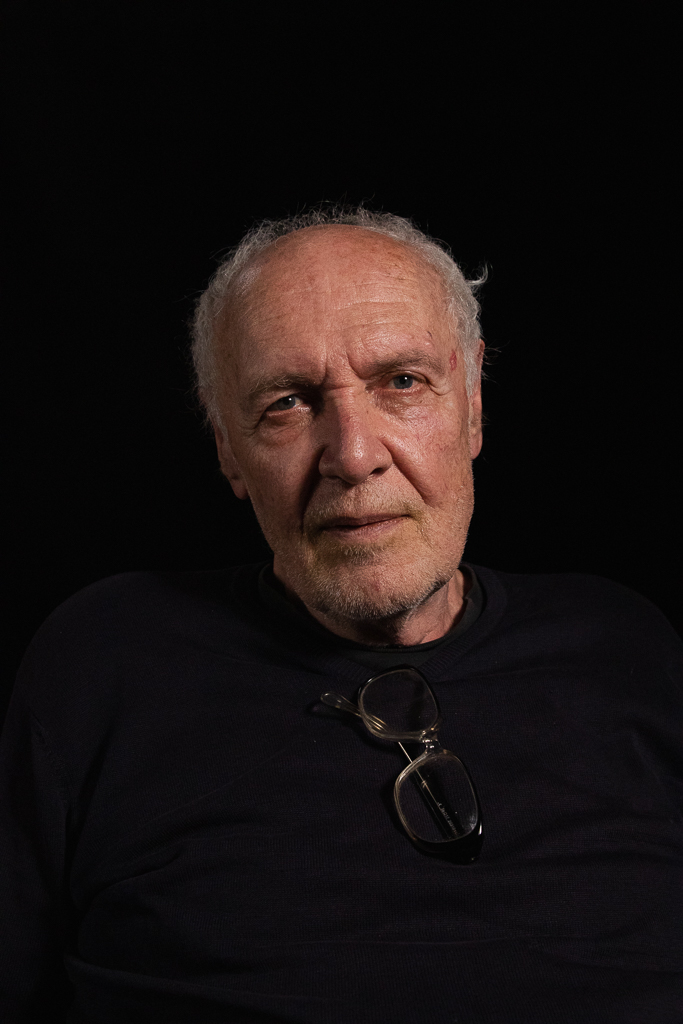

Václav Trojan was born on 6 December 1945 to a family of a well-known composer, Václav Trojan senior. He grew up in an environment where creativity and inspiration was a norm, as his father taught him both the history and theory of music, and at the same time he would let him pursue his own interests, especially physics and chemistry. After graduating from grammar school, Václav Trojan started attending the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, but left the school after two years. He tried to find his own way, working as a lighting electrician at the Na Zábradlí Theatre, he volunteered for the Ostrava coal mines, but left after just three months; then he started his compulsory military service, but was discharged after ending up in a psychiatric hospital. After that, he started attending the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, majoring in sociology and philosophy, witnessing the ‚free‘ atmosphere of the Prague Spring. In 1969, he won a scholarship to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but in the end, he would refuse the opportunity, knowing that it would mean that he would have to leave the country for good. He decided to stay in Czechoslovakia, working at the Research Institute for Mathematical Machines. He met several Charter 77 declaration petitioners at the place, joining their ranks as soon as in December 1976. By signing the Charter 77 declaration, he made himself a target of the State Security, yet he could keep working at the Institute.