We couldn‘t go with a gun against a cannon

Stáhnout obrázek

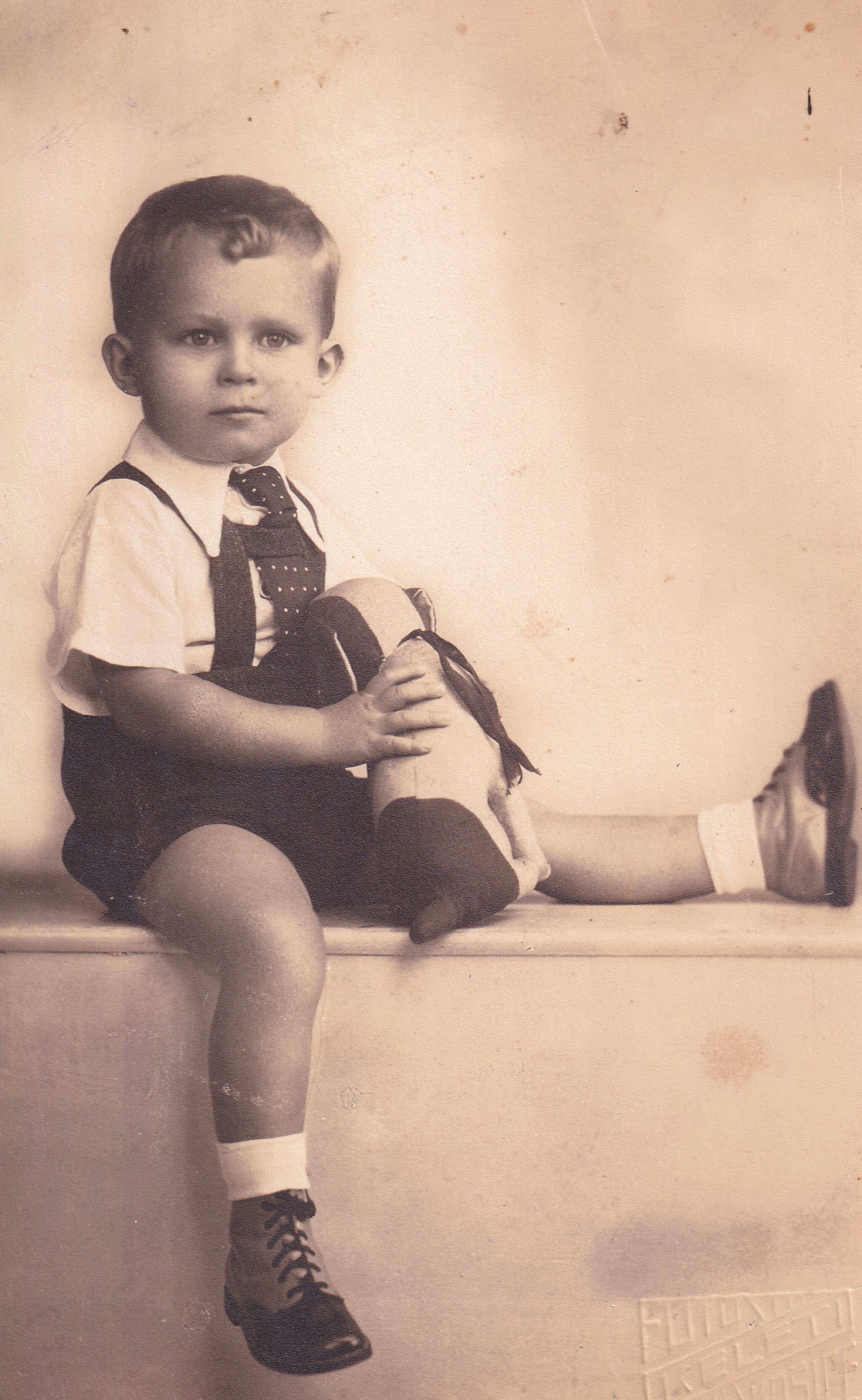

We couldn‘t go against a cannJaroslav Skopal was born on September 24, 1936 in Košice in a mixed Czech-Slovak family. After the proclamation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the Skopals had to leave Slovakia. They headed to Přerov, where Jaroslav‘s sister Dagmar was born later. As a teenager, the witness was involved in the activity of the renewed Sokol unity in Přerov after the war. He studied briefly at the grammar school and later on at the twelve-grade school. After graduation he went to study in Prague and successfully graduated from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the Czech Technical University. After shortened military service he worked for several months in Branecke Zelezarny. In 1960 he joined the company Přerovské strojírny, where he stayed all his life. He worked as a research and development worker in the field of automatic process control of technological equipment, which the company produced for domestic market as well as for export. In 1967 he joined the Czechoslovak Socialist Party (ČSS) and since the end of 1968 he was a member of the Czech National Council. At the end of September 1969, he resigned from his post. He did not pass the political screenings the following year, which meant a number of sanctions at work and interrogations and persuasion for cooperation with the State Security. Following his father‘s model, in 1963–1990 he devoted himself to training activities in Spartak Přerov Engineering Works. After 1989 he returned to politics, later only at the municipal level. Since 1997 he has been working as a pensioner in the field of quality consultancy for ten years. In recent years, he has published a number of publications - Against the Stream of Time (his own memoirs), Struggles with Totalitarianism and Escape for Freedom (life stories of Rudolf Lukaštík and his friend Bohuslav Ečer), portrait of General František Moravec or The End of One Big Party? Devoted to the Czechoslovak Socialistic Party and its successors. In 2019 he lived in Přerov.on with a gun