Doma je tam, kde si to protrpíte

Stáhnout obrázek

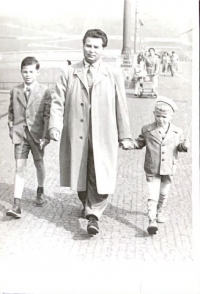

Miroslav Šik was born on the 7th of March as a son of Ota and Lilly Sik. As a child, he experienced what it means to be a child of a high-ranking Communist official. There were many advantages to such a status that included the possibility to travel abroad or buy expensive Western clothes of which the children of common Czechoslovak citizens could only dream. The family fortunes radically changed after the August 1968 occupation. The economist Ota Šik was one of the foremost advocates of the liberalisation process of the 1960‘s and he decided that the family which was spending their holiday in Yugoslavia would not return to Czechoslovakia. The Šik family spent the first few days after the invasion on the private island of Josip Tito and before they were ready to emigrate to Switzerland they used a govermnemt mansion in Beograd. From there, the Šiks moved to Switzerland. Miroslav had problems adapting to life in emigration and during the first year, he kept running away to Czechoslovakia. His brother Jiří refused to accept living as a refugee; he returned to Czechoslovakia only to leave again after 12 years. Miroslav studied at a high school in Basel and then architecture at the ETH in Zurich. The turning point in his life was meeting with the Italian architect Aldo Rossi whose seminars he attended. After having graduated in 1979, he got a research position at his alma mater. During the 1980‘s, he started developing the idea of the so-called analogous architecture whose aim is to blend in with the environment without showiness and unnecessary décor. In 1990 – 1992, he taught at the Faculty of Architecture at the CTU and since 2018, he has been the head of Architectural design at the Academy of Arts in Prague. He has been suffering from a feeling of not belonging which stems from the fact that he did not live his childhood in Switzerland. After the fall of Communism, he returned to his home country but not permanently. He lives alternately in the Czech Republic and in Switzerland.