She refused to go out with the yellow Star of David on her lapel

Stáhnout obrázek

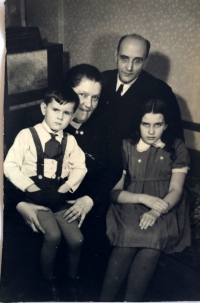

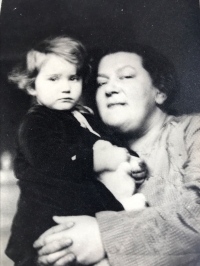

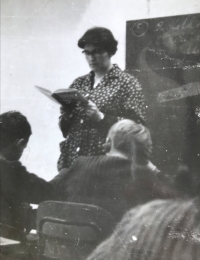

Eva Kotková, née Beránková, was born on the 5th of October in 1932 in Prague. Her mother, a physician, was from a Jewish family from Nymburk, her father was originally from Frýdek-Místek. As a result of the ruling of the 27th of March of 1939 of the medical board, Jews were not permitted to work as physicians any more, nor did Eva’s mother. Eva’s grandmother was deported to Terezín and later murdered in Treblinka. Until January 1945, father was able to protect his family as his was a mixed marriage. When Eva’s mother was summoned for a transport, she decided to undergo a surgery. Two days later, she died of a heart infarction. After war, Eva became a teacher and joined the Communist party. In August 1968, excited by the changes in society, she participated in the Meeting Extraordinary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, the so-called Vysočany Meeting. After the normalisation interviews and background checks, she was expelled from the Communist party, she had to leave the school and the only jobs she was allowed to do were the manual ones. Nowadays, she lives in Prague with her children and grandchildren.