I lived through a lot of fear; I saw the world without embellishments

Stáhnout obrázek

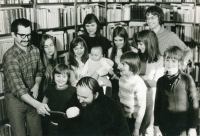

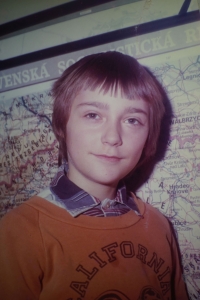

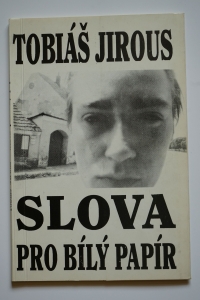

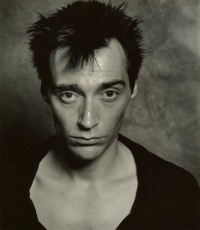

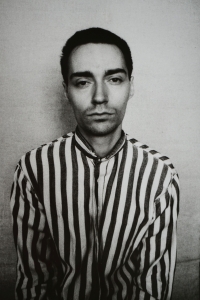

Tobiáš Jirous was born on the 3rd of May 1972 as the son of art historian Věra Jirousová and philosopher Jiří Němec. His mother was however married to Ivan Martin Jirous who wanted to be entered as the child’s father. All of them were a part of Prague dissent and all of them later signed the Charter 77. These circumstances formed Tobiáš’s childhood and youth when he lived in constant fear. The family life was complicated and it lacked any financial security. At school, he felt not accepted by both teachers and schoolmated who often harassed him. Until he was twelve, he lived mostly in Prague, he spent some time in the so-called underground houses. He likes to recall the holidays spent with the Havel family in their house in Hrádeček. When the State Security pressed his mother to emigrate during the Operation Clearance, they moved to the countryside, to Kostelní Vydří in Southern Bohemia, where his younger sister, Sára, was born. They were not left to live in piece, though. Tobiáš Jirous recalls ruthless house searches and a constant worry that his mother would be imprisoned and he would end up in institutional care. In this situation, he couldn’t even think about going to a secondary school so he started his apprenticeship at a gardeners’ trade school. At the time of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he was in his last year and he started his work career as a gardener, factory worker and a night guard in Prague. Long after the revolution, he still helped to provide finances for his family and to care for his sister. Later, he became aware that he had an issue with living in some order and accept that even he could have the options he wouldn’t have had thought about. In 1998, he started to study at the Academy of Fine Arts but after two years, he decided to leave because he did not like the atmosphere of the school. Gradually, he was establishing himself in arts and the list of his vocations is long: writer, journalist, drummer in the DG 307 group, frontman in the groups Juniors, Ultrasweet, Hifi Heroes, and The Models, as an independent DJ, nowadays he owns a recording studio. At the time of recording in 2022, he and his wife lived in Prague.