I think God has blessed me with always being in the right place at the right time

Stáhnout obrázek

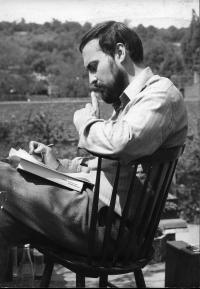

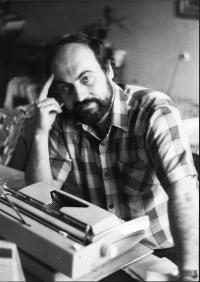

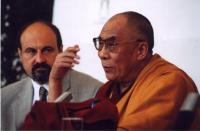

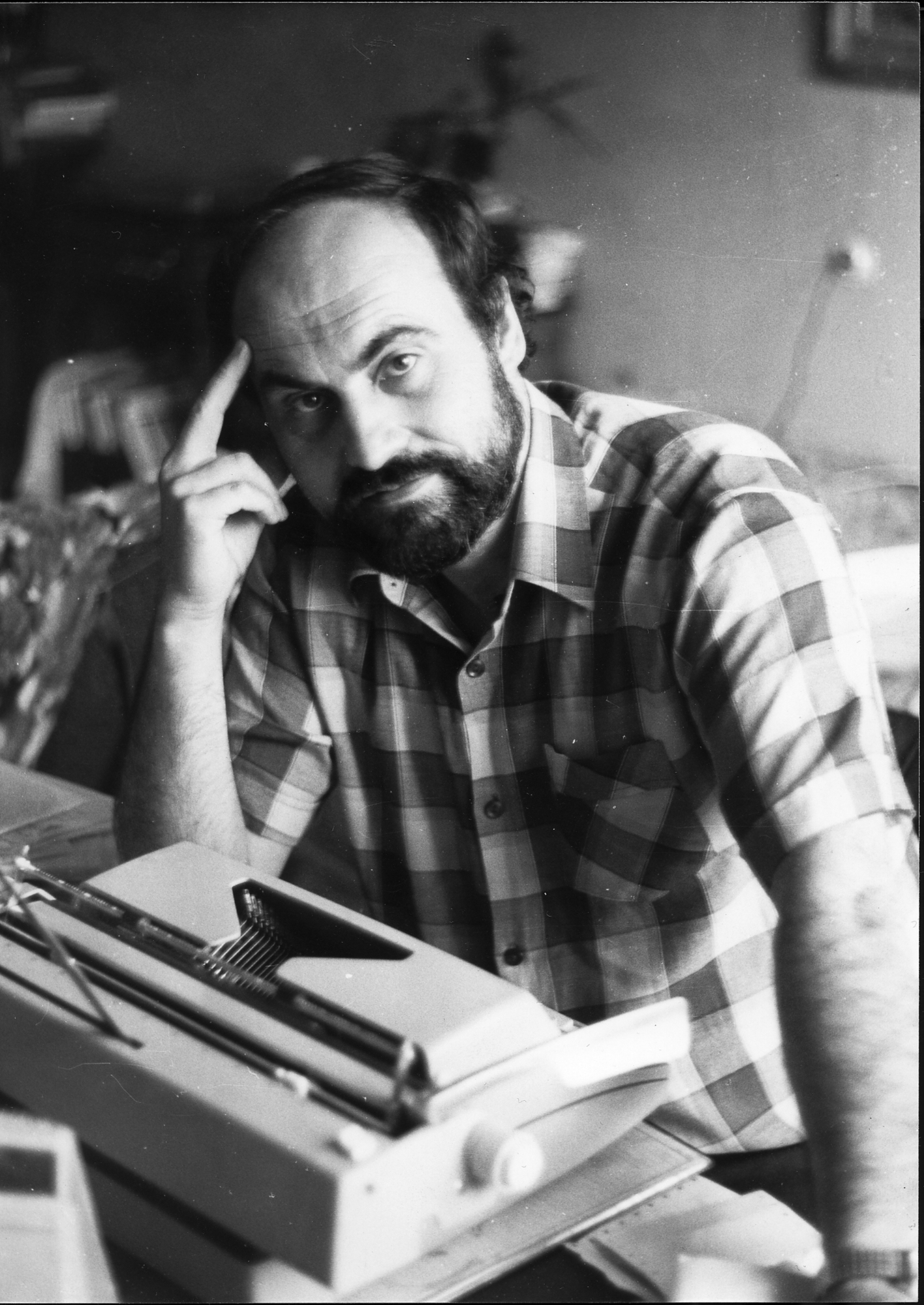

Mons. Prof. PhDr. Tomáš Halík Th.D. was born on the 1st of June, 1948 into the family of the literary historian, PhDr. Miroslav Halík, and his wife Marie Halíková (née Wimmerová). He studied Sociology and Philosophy in Prague from 1966 to 1971. The Soviet invasion of 1968 started when he was studying in Britain. At that time he decided to return home and stay in Prague. For political reasons he was banned from university teaching until 1989, so between 1970 and 1990 he worked as a sociologist, psychologist and as a psychotherapist. Halík was active in the cultural and religious dissent, which involves flat seminars, samizdat and underground churches. IIn 1978, he was secretly ordained as a Catholic priest (in the former GDR), and in the 80´s he was one of the closest fellow servant of the cardinal Tomášek. After 1989, Tomáš held many important positions within the Church, and was an advisor of the former president Václav Havel. Currently, he is a professor at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, the rector of the University Church of St. Saviour in Prague, and the president of the Czech Christian Academy. In 2014, he was awarded the Templeton Prize for progress in research and findings related to spiritual matters.