As a child I often wondered why my father had a number tattooed on his forearm

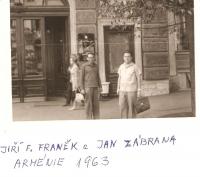

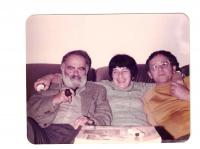

Věra Dvořáková, née Fraňková was born on March 2nd, 1953 in Prague into a Czech-Jewish family. Her father and grandfather were imprisoned in concentration camps during WWII - the former for his Jewish ancestry, the latter for political reasons. Věra‘s parents were scholars of Russian studies. In the 60s, her father, Jiří, lectured at Prague‘s Charles University, Faculty of Arts and later at universities in Western Germany. Following the post-1968 invasion purges, her parents lost their jobs and had to take up unskilled labor. In the 70‘s and 80‘s, the family was in contact with Czech dissidents, helping them with transcribing and distributing illegal materials. During the so-called ‚normalization era‘, Ms. Dvořáková taught Russian and physical education at Prague‘s elementary schools. After the Velvet Revolution, she became a member of the right-wing Civic Democratic Party. At present, she serves as a director of Jewish Liberal Union.