A man can do everything he really wants to do

Stáhnout obrázek

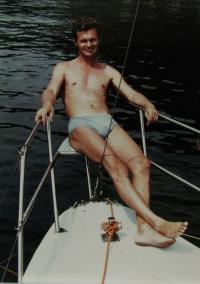

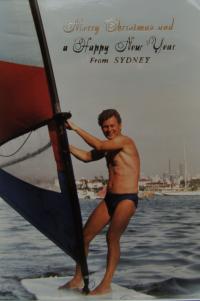

Josef Dušek was born on 17th January, 1941 in Starý Klíč no. 96 (region Domažlice) to the husbands Josef and Jarmila Dušek. His father was a member of the state police and in 1951 was arrested as a guide. The witness and his mother, who got divorced, and his sister moved to Pilsen, where he apprenticed a brick-layer. He worked in a construction company and became a member of the Aeroklub in Pilsen, from which he got also expelled due to family relations. And so he switched to boats. In August 1964 he left as a perspective communist to England with a trip, from which he never came back and with the help of immigrant unions he resettled a year later to Australia. He settled down in Sydney, where he worked as a roofer; he build a trimaran Dalibor and got a intimate relationship with Jane Gloore. In 1972 he won an Australian citizenship and then he managed to cancel his Czechoslovak citizenship to cancel the immigration punishment at the same time. So in 1977 he could go back to his country again. In the next decades he led a double life; during Australian summer he worked in Sydney and in winter, during the European summer, he was traveling with many companies and did exhibition cruises. He was coming closer and closer to Europe. For ten years he was driving tourists for a certain hotel in a lagoon La Manga del Mar Menor near Cartagena. Following the velvet revolution he automatically got back his native citizenship. In the last years he began building his home back in his country. For four years Josef Dušek has been living pernamently in Sušice and Dalibor is waiting for a buying in the Orlík dam.