As a child, I became an enemy overnight

Stáhnout obrázek

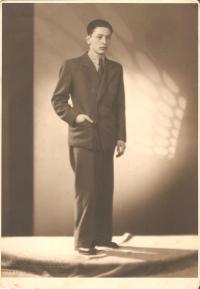

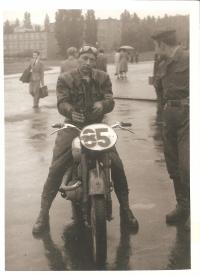

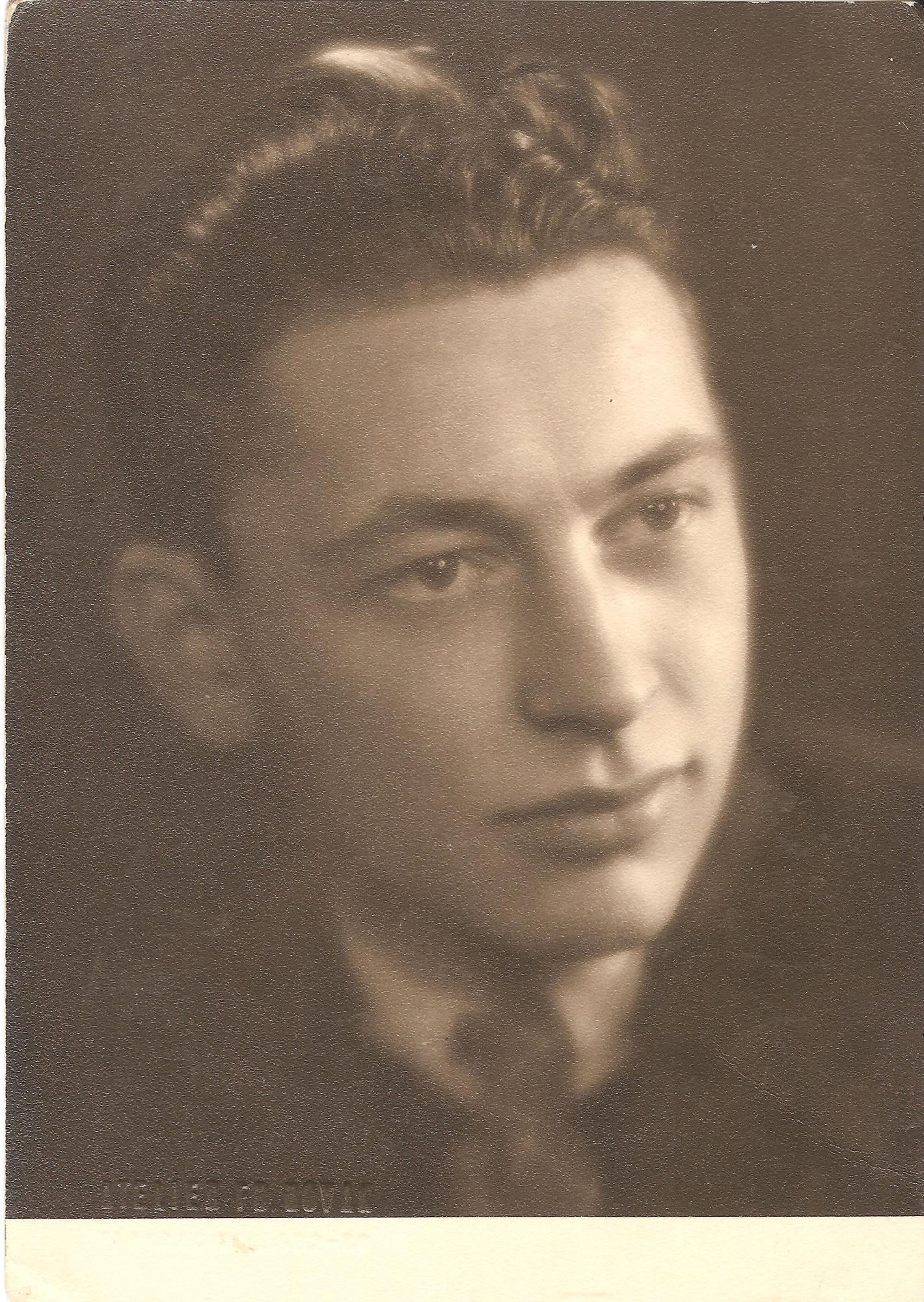

Oskar Dub was born in Kadaň in 1924 into a mixed German-Jewish family. His father was a Jewish businessman, who managed to secure the family financially, allowing Oskar to enjoy carefree childhood. This changed, however, after the signing of the Munich Treaty in September 1938 and the subsequent German takeover. The family had to leave the Sudetenland region under dramatic circumstances, eventually finding a safe haven in Prague. The situation became even worse after the declaration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia due to anti-Jewish regulations. Oskar and his father had to wear the Star of David and respect anti-Jewish rules. His father got a job in the Jewish Community in Prague, which protected him from being included in a transport. Their other Jewish relatives were not so fortunate; they were deported and never returned home. In autumn 1944, Oskar was deported to Terezín, where he was reunited with his aunt and cousin. From Terezín he was transported to the Klettendorf labour camp. He worked on construction of air raid shelters in Dresden. He experienced the Allied bombing of the city and even helped remove the debris. Near the end of the war he managed to escape during a transport march and return to his parents in Prague. However, the war was not yet over; Oskar was forced to spend the final days in the camp in Hagibor, Prague. When the family returned to Kadan, Oskar‘s mother was threatened as a Nazi supporter. His father managed to save her from deportation. Oskar settled in Kadaň, started a family and now enjoys spending time with his two great-grandchildren.