During the Velvet Revolution, people were so nice to each other. Sadly, it doesn‘t happen all the time

Stáhnout obrázek

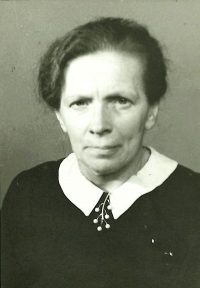

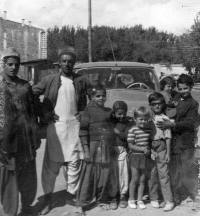

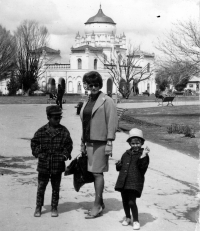

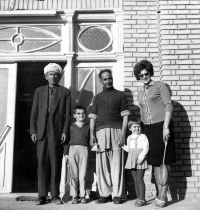

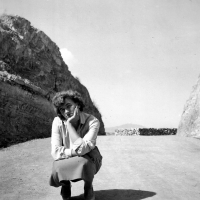

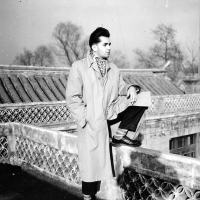

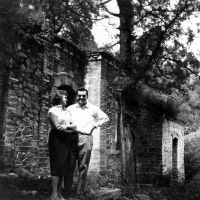

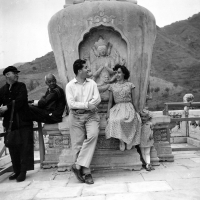

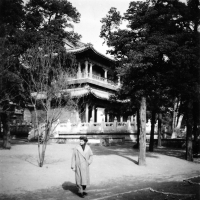

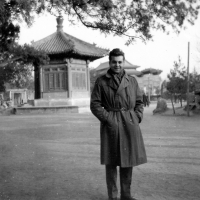

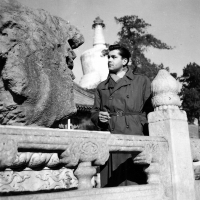

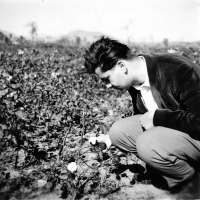

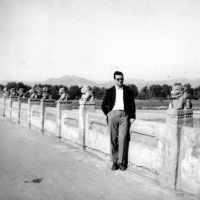

Květa Dostálová, née Perníková, was born on 20 June 1933 in Ostrava. She grew up in a family house in Klimkovice. Her father had a tailor‘s shop, but after February 1948, he was forced to join a cooperative. She witnessed life in Klimkovice after the occupation of the Sudetenland in 1938. In August 1944 it experienced the bombing of Ostrava. She witnessed the liberation struggle and the air raid on Klimkovice in 1945. She also witnessed the heavy fighting of April 1945. She studied Russian and Czech at the Faculty of Philosophy in Brno. She married Ivo Dostál, who had a degree in English and later served as a diplomat. In the 1950s, she followed him to China, where he had served at the Czechoslovak embassy. She had taught Czech in Beijing. In the 1960s, her husband had been working as a diplomat in Kabul, Afghanistan. She followed him with their children, working as a Czech language teacher. In 1968, her husband was recalled from Kabul because of his protest against the Warsaw Pact troops invasion of Czechoslovakia. He hadn‘t been allowed to hold public office until 1989. He was forced to do blue-collar jobs only, working as a foreman in a glass-works for example. The witness had been teaching at several secondary schools in Prague. In November 1989, she supported the Velvet Revolution with her students.