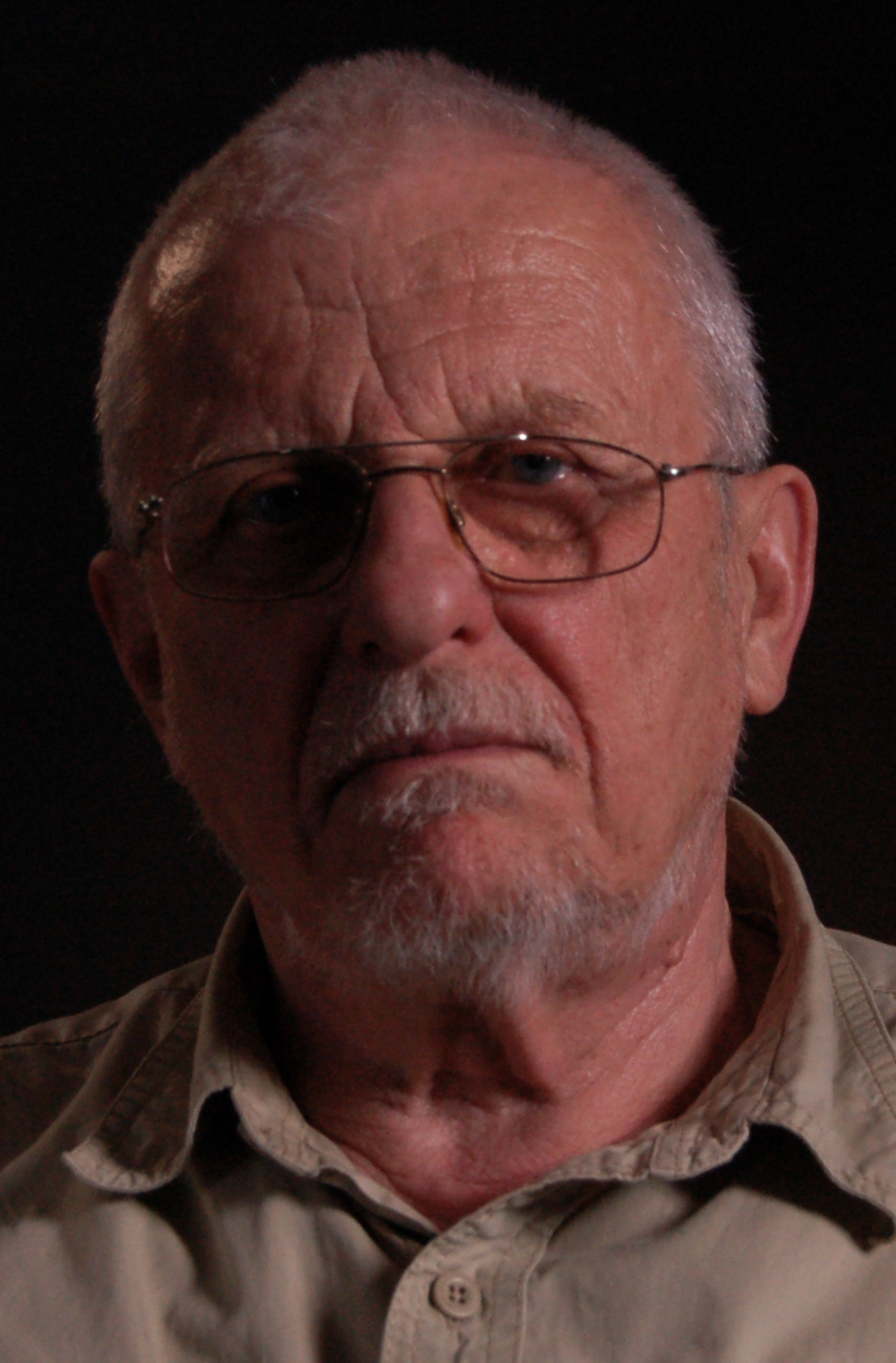

"The only form of distinct persecution that I experienced, was that they took me into a forest and beat my mug in. But just a little bit, I must say. But on the other hand they took me out into a rather hostile forest. It was like this: I used to go occasionally to visit this one acquaintance of mine, who was simply put quite a bit active in the Charter [77], and that was Ladislav Hejdánek. Ladislav Hejdánek had, as it was for a person so active, his own surveillance. There was a cop there, a man in uniform, and he wrote down who came in and who went out. It was unpleasant, of course. I kept on going there, and because I had too many marks, and they happened to start up that operation, I don’t know who came up with it at the State Security HQ, that they’d intimidate people with actions of a more brutal character, so the day before it happened to me, they got a grab on Ivan Medek and took him somewhere into a forest, there they punched him in the abdomen and left him to his fate. Ivan Medek later emigrated. Well, and the next day I had the awful good luck that before I went to visit Hejdánek, I found out the exact scenario, how they... some acquaintance stopped me on the street and told me what had happened to Medek. So afterwards when I went there, the StB men [State Security] arrested me, took me to Bartolomějská [Bartholomew Street, the infamous State Security HQ], and after that I looked on in horror as the same scenario was enacted on me. Because they did it so, that they kept me there until about eleven p.m. for no reason. That was interesting, because the operation chief, the one who was in command, he was completely drunk. As a doornail, simply. He could hardly articulate. He was telling me something about dicks or something of the sort. There were three boys there guarding me. Two of them were dead embarrassed, one of them was kind of keen. Then they sat me into a civilian Škoda [Czech car], to take me home they said. I told them I didn’t want to, but they said: no, no, this and that has to be done. I knew what it meant. They took me to Římská [Roman] Street, I said: 'I don’t live here.' They said: 'No matter, you said Římská, out of the car.' So I got out, and the StB man was handing me my ID card, I tore it out of his hand and started legging it like crazy. Now that complicated the scenario somewhat, as it took them quite a while to catch me. And that surprised me, as the three of them were quite the muscle, and when they caught me in the end, they were awfully tired and out of breath. I thought the policemen had to have some sort of training or something. They caught me at the corner of Římská and Italská [Italian Street], where there were people normally passing by. They pretended to be terrorists. The one chap had his hands on them and tried to defend me, and they told him: 'Keep going, keep going!' That’s odd, when terrorists speak like... And then there were some girls standing to the side, watching and they said: 'Surely they can’t afford to do this!' So it was obvious to them. I could’ve escaped them, easy, they couldn’t have kept on chasing me there, there were lots of people walking about, even though it was at night. But I reckoned that I had it coming in any case, so I let them grab me, they pushed me into the car, blindfolded me, put on the shackles, and drove me off somewhere, I didn’t know where. They drove about an hour, after the hour they chucked me out of the car, gave me a bit of a beating. They were pretty mad, they hadn’t counted on having to run around after me. Maybe I could’ve given that a miss. I don’t know if anyone got into trouble because I tried to defy them, I’d be deeply sorry for that. So they chucked me out and drove off. I was really glad when I saw the red lights leaving. Then I had to find out where I was, I had no idea where I was. So I found out I was between Příbram and Sedlčany, I found out which direction Příbram was in, it was closer as I found out from the bus stops, so I walked to Příbram, got on a train there, I had to wait about three hours in the night, and I made it back to work just right, at seven in the morning. That’s the biggest adventure I experienced with State Security throughout the whole functioning of the Charter. Afterwards, after 1987 I had all sorts of different experiences with them, but none so colourful as this."