To write is convenient

Stáhnout obrázek

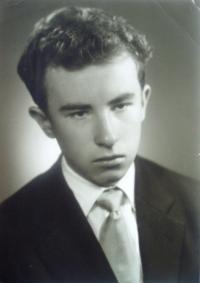

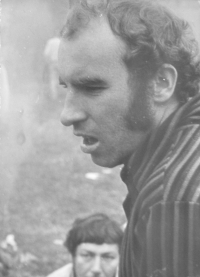

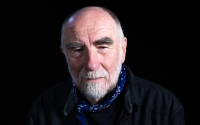

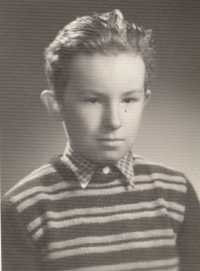

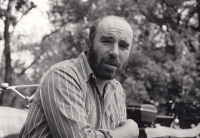

Ivan Binar was born on 25 June, 1942, in Boskovice. After the war, his family moved to Hradec near Opava where his father worked as a lawyer in the Branecké metal works. Ivan‘s father was fired from the works after February 1948 as he was proclaimed a „bourgeois element“. The family then moved to Opava where Ivan continued his secondary studies until his graduation. In 1963 Ivan graduated from the Pedagogical Institute in Ostrava, having studied Czech linguistics, history and art. During his university studies, Ivan enjoyed stage acting in the theater „Pod okapem“. He‘d known some of the members of the ensemble since his youth. After he completed his compulsory military service he worked as a teacher in the years 1963-1965. He also worked in the regional youth center in Ostrava. In 1968 he became the editor of the magazine „Tramp“. Together with his friends from the dissolved ensemble of the „Pod okapem“ theater, they founded the theater „Waterloo“. It was here that they performed the play „Son of The Regiment“ based on a novel by Valentin Katajev. Mr Binar was then arrested in 1971 and taken into custody. He was released in the same year but was shortly afterwards found guilty of agitation and sentenced to 12 months in jail. From August 1972 to February 1973, he was incarcerated in the Bory prison in Pilsen. After his release from prison he had to work in manual professions. He was also meeting friends from prison, writing and publishing. In January 1977, he signed the „Charta 77“ whereupon he was given two options: cooperation with the secret state police or emigration. He chose the latter and emigrated with his wife and children to Austria in May 1977. He settled in Vienna where he first worked as a china restorer. He then started his collaboration with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Vienna. In the years 1980 - 1983 he also worked as an interpreter in the refugee camp Traiskirchen. Since August 1983 he worked for RFE/RL in Munich where he was responsible for press monitoring. He later became the editor of the program „Voices and Receptions“. After the Velvet revolution, he moved to Prague in 1994 to work for the Czech edition of RFE/RL until it was shut down in 2002. In November 2002, he became the president of the Writers‘ community. He didn‘t run for the post for a second time. In 2010 he lived with his wife in Prague and wrote books.