Communists not communists, we all lived here

Stáhnout obrázek

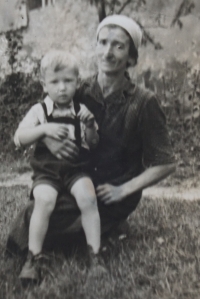

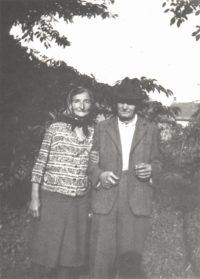

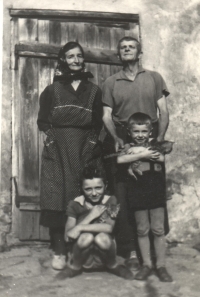

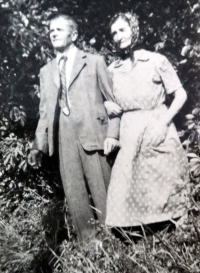

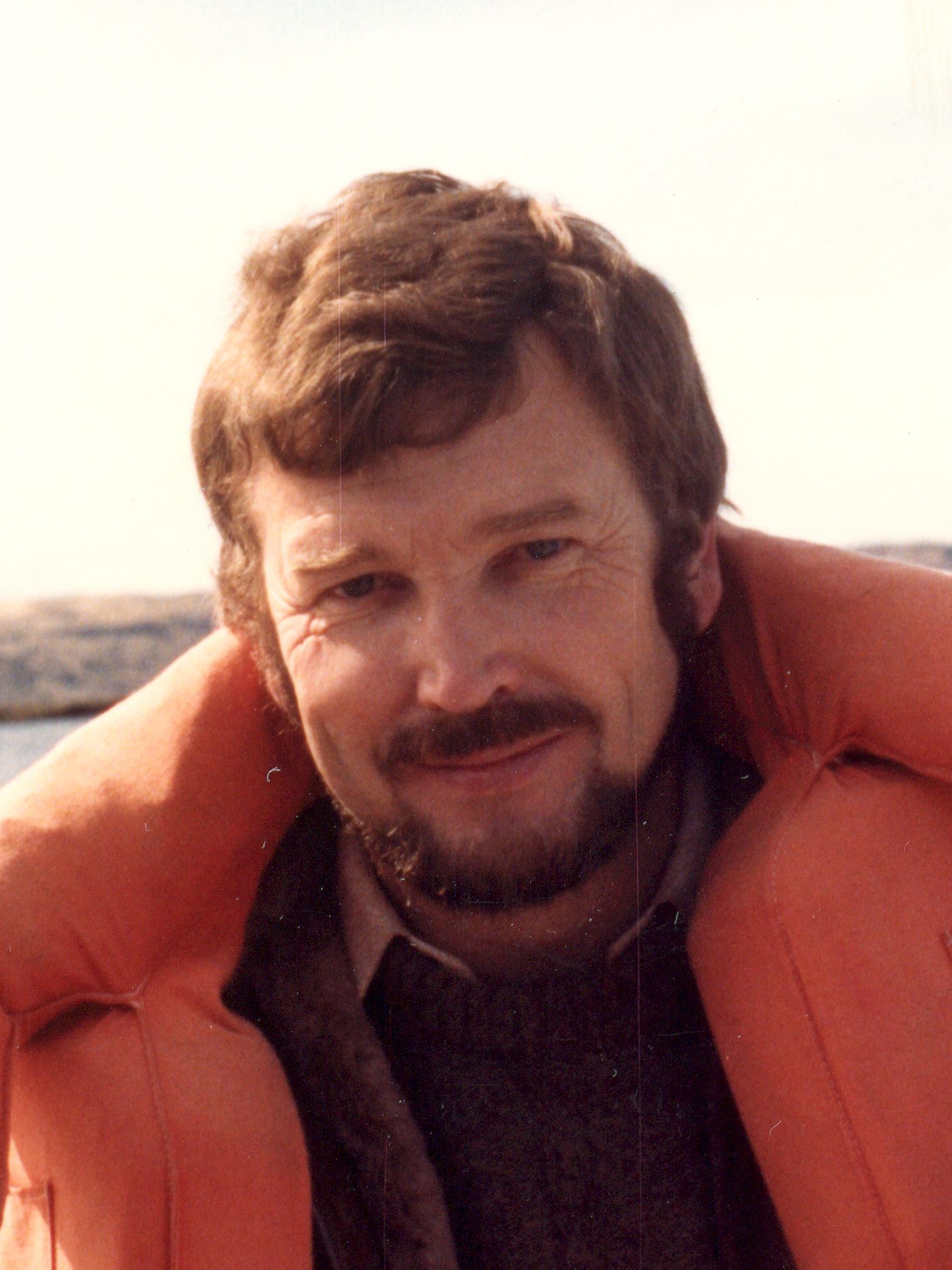

Josef Bábek was born on 3 May 1941 in Nový Dvůr near Kvasice. His father, Rostislav Bábek, fought as a Czechoslovak legionary on the Eastern Front during the First World War. After the war he bought a farm in Nový Dvůr. At the end of the war, German soldiers briefly stayed with them and shelled their house when they left. After the war, the family lost most of their savings in deposits. The witness´s father was imprisoned several times for his negative attitude to collectivization. When he was in prison in 1953, his mother and Josef were evicted from Kvasice to Topolany near Olomouc, where they lived in very poor conditions. Because his parents went to work in Topolany in a cooperative farm, the witness got a good cadre assessment and was allowed to study at the railway apprenticeship of the state labour reserves in Olomouc. In 1960 he joined the military service in Hranice to join a heavy artillery brigade that worked with Scud missiles. After the military service he graduated from the Secondary Technical School in Zlín and worked at the Czechoslovak State Automobile Transport (ČSAD). He went to work at the Czechoslovak Automobile Repair Plant (ČSAO), where the director fired him because he distributed a petition to be signed during the Prague Spring. He went to work for Uničovské strojírny, for which he travelled abroad to assemble and service excavators. Before his trip to Romania, he received a bad assessment from his previous job from the director of the ČSAO and was transferred to northern Bohemia, where he worked as an assistant riveter. In West Bohemia he was given the task of building a mine machine and was allowed to return to the service department when it was completed. He went on to assemble and service excavators in Spain, Argentina, Sudan and Venezuela. After the revolution, he bought the ČSAO premises in Litovel and founded a company trading in working machines, which he later sold. In 2023 he was living in Střelice near Uničov.