You can‘t look forward to anything in communism and that sucks

Stáhnout obrázek

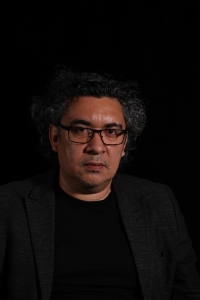

Carlos A. Aguilera was born in 1970 in Havana. He and his mother lived in the El Cerro district near the city centre. As a child, Carlos did not stand out in any way, his family did not differ from the majority of the Cuban population in social and political behavior. He used to go to the Pioneer organization and his mother worked as an accountant. In the 1970s, their lives were marked by constant power cuts and a lack of money. These are the main things that Carlos recalls of this period, which was very difficult for almost all Cubans. The lack of basic things was nothing extraordinary at that time. A little later, when he was about twelve years old, he slowly began to get acquainted with the world of literature. Since then, his life has been affected by books. He knew from the beginning that one day he would become a writer. With this in mind, he became a part of various literary circles and workshops, where he had the opportunity to meet people with the same interest. He attended public readings in the homes of Cuban writers and, together with several friends, they founded a literary group that later turned into one of the most important voices of contemporary Cuban literature - Grupo Diáspora (s). The group published a magazine dealing mainly with such topics as the relationship between an intellectual and the state. The goup spoke out against generally accepted realism in literature and culture. They perceived the writer primarily as a performer and a person who thinks about literature. Due to the specific character and ideological orientation of the group, the Cuban authorities soon became interested in its members. Nevertheless, Carlos managed to publish some relatively successful books. In 2001, he was offered the German PEN club scholarship. At first, however, everything indicated that he would not go anywhere due to his political conviction. This eventually changed after the pressure, which was exerted on the Cuban authorities not only by the German PEN club, which threatened to make Carlos‘ case public, but also by the mayor of Bonn, where he was to stay during the scholarship. After leaving Cuba, Carlos has never returned. As an author, he was a success and won many literary scholarships in several Central European cities. He stayed in Germany, Austria and finally in the Czech Republic, where he still lives with his Czech wife. He continues to write, his books are translated into many foreign languages. He is also involved in the InCubadora project, which supports a network of independent libraries in Cuba.