I’ve always regretted that we didn’t emigrate

Stáhnout obrázek

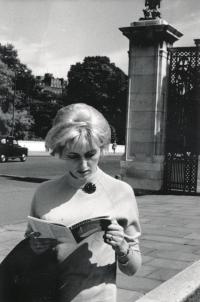

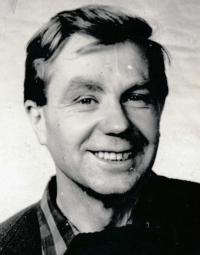

Eva Mašková was born on 8 March 1937 in Brno; her father Václav Urbánek was awarded a post at the Supreme Inspectorate in Prague. When she was thirteen the family moved to join him. Before that, as a child, she witnessed the bombing and the liberation of Brno, including the lynching of local Germans. In the 1950s she gained employment at the Research Institute of Aviation in Prague; her department was later reassigned to Motorlet. There she met her future husband Zdeněk Mašek, an expert on aircraft engine development. During the political profiling following 1968, her husband refused to agree with the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the armies of the Warsaw Pact. He was expelled from the Communist Party and barred from advancing his career. The family was not allowed to travel abroad, their children had difficulties when applying to schools. Eva Mašková tried out several different jobs; her whole life she has regretted refusing her husband‘s request that they emigrate together.