Student connection of the Brno-Warsaw branch of solidarity

Stáhnout obrázek

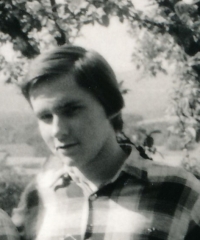

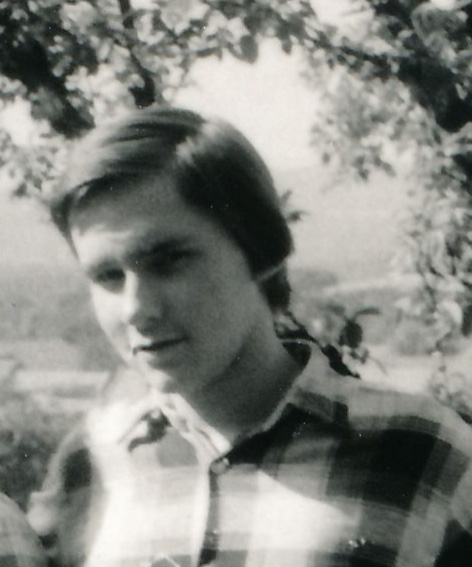

Rudolf Vévoda was born on July 27, 1964 in Třebíč. He grew up in Brno, where he graduated from grammar school in Cpt. Jaroše. He read a lot and was interested in history and after graduation he started to study at the Faculty of Philosophy of Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Brno, where he studied Czech language and history. During his studies he became a practicing Christian. He became a member of the Saint Gorazd Association, with which under a strict conspiration he went around churches and various events with a band of chants coming from the Eastern Liturgy and reading from legends. After getting to know Petr Pospíchal, he got into the group of Charter 77 signatories and became friends with Jaroslav Šabata. He himself sought contacts and meetings with representatives of the Catholic dissent, including Josef Zvěřina, František Lízna, Otto Mádr and Josef Adámek. Together with Petr Pospíchal, they were at the foundation of the Brno-Warsaw branch of Polish-Czechoslovak Solidarity. He was interrogated several times by the State Security. He contributed to samizdat magazines, such as the Moravian Community. He graduated in December 1988 and on March 1, 1989 enlisted for basic military service. After six weeks of pretending health problems, however, he was released and decided to live in Prague, where he worked primarily with Tomáš Dvořák from the Independent Peace Association and lived through the end of the communist regime.