I learned everything necessary on my own

Stáhnout obrázek

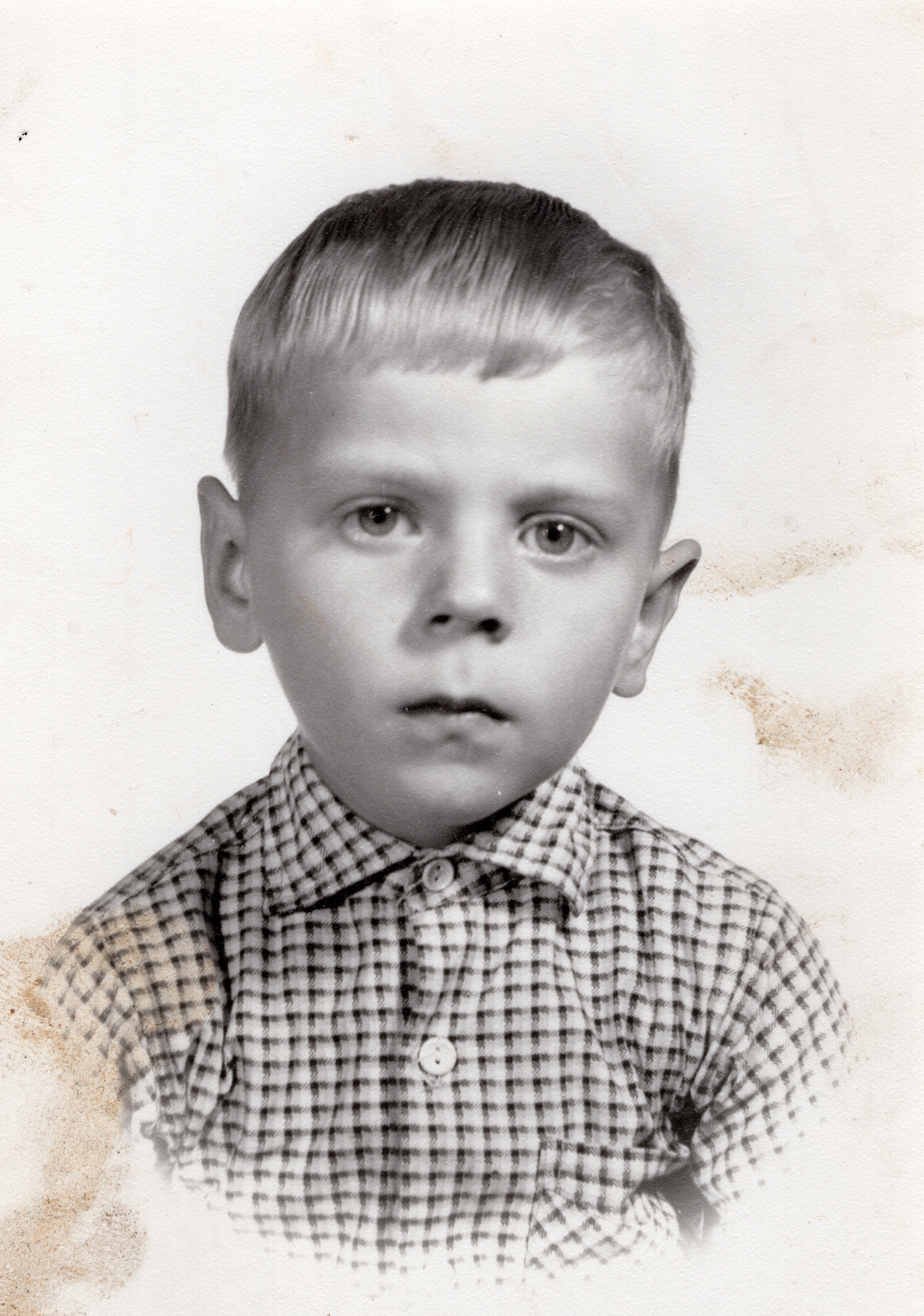

Miroslav Václavek was born on 19 August 1965 in Rýmařov. His father Vladimír Václavek Senior had to join the Auxiliary technical battalions during his military service in the first half of the 1950s as a politically untrustworthy person. The Václavek family always spoke openly at home about everything the adults minded about the communist regime. Moreover, Miroslav was affected by western music, literature, and daily listening to Radio Free Europe. When he was thirteen years old, he decided to take the law into his own hands and he fired an air rifle from a dormer window at a Soviet truck, which had to stop there because of a malfunction. Due to his non-childish radical approach, Miroslav often faced bullying by the teachers at elementary school and also a vocational school in Bruntál. He had to face more bullying during his military service. When he returned from his military service in 1987, he and his friends-dandies went to Valtice for wine festivals where they were brutally beaten by police because of their long hair. Miroslav Václavek signed and shared the declaration A Few Sentences in the summer of 1989 and he took part in demonstrations in Šumperk during the Velvet Revolution. His older brother was a famous musician Vladimír Václavek and his uncle was a member of the Devětsil Union and a literary theorist and critic who died in Auschwitz in 1943. Miroslav attributes the genes that influenced him so strongly in the field of literature to him. He published a poetic-prosaic miniature Člunky (Boats) in 2010. Four years later he published an anti-war novel Železné včely (Iron Bees) in the edition of Knížní klub Publishing House and the novel was awarded the prize of the publishing house. Miroslav Václavek published a poetry collection S rybí kostí v krku (With a fish bone in the throat, 2015) with the Brno underground publishing house Uši a Vítr, and his texts are used by many alternative bands and also by his brother Vladimír. Miroslav Václavek lived in Šumperk in 2021 with his wife Alena. They raised two daughters, Martina, and Veronika.