They brainwashed us with Communism from childhood

Stáhnout obrázek

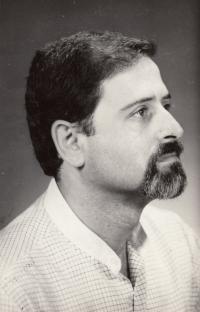

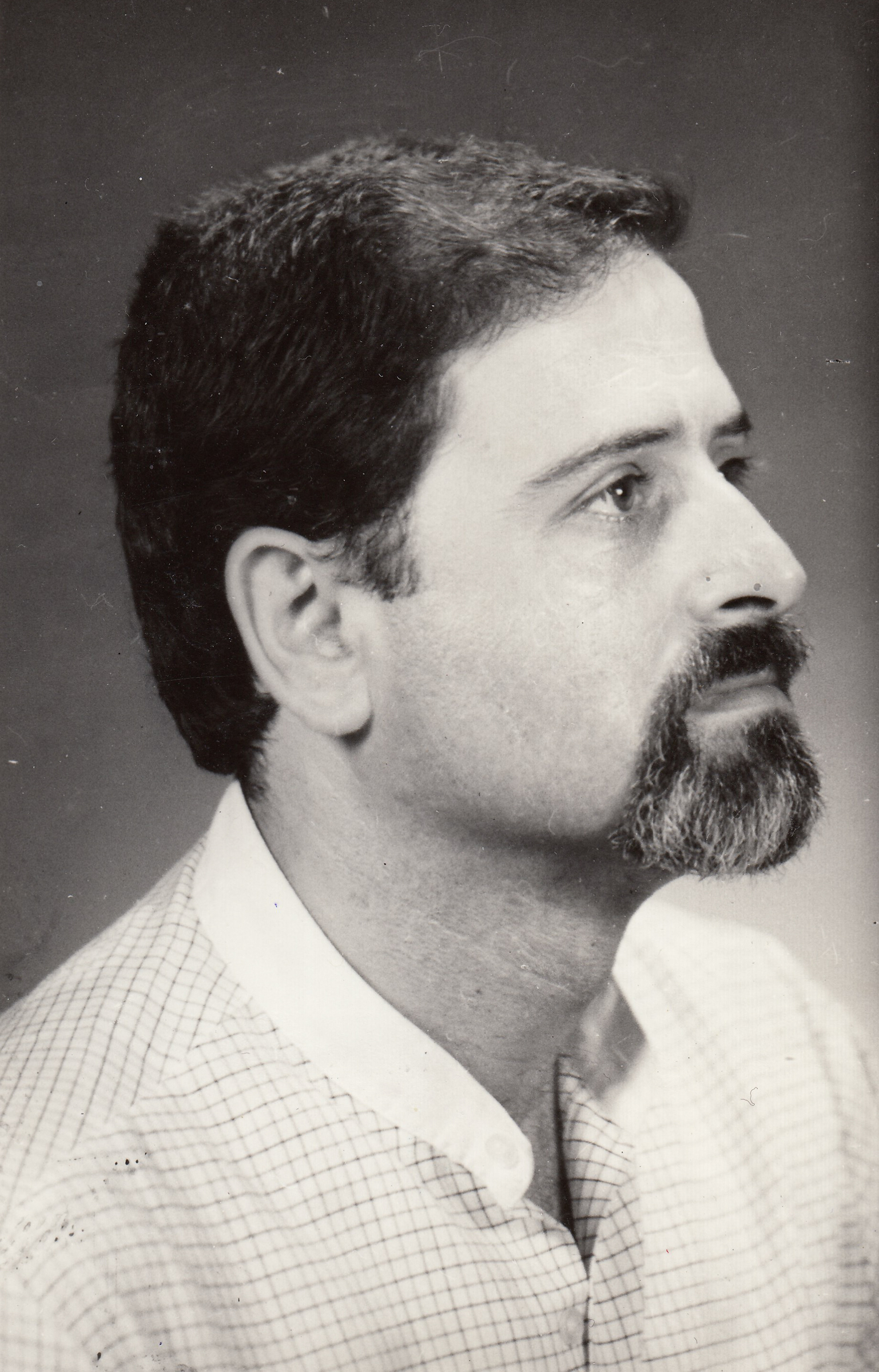

Vasil Samokovliev was born on 22 July 1946 in Bulgaria, into a Greco-Bulgarian family in the city of Pomorie by the Black Sea. A year after his birth Bulgaria was seized by the Communist Party, which both of his parents joined, although his father was expelled many years later. After attending primary school, the Communists chose the talented Vasil for a language school, where he was to learn French. However, he did not want to learn the language of capitalists and insisted on learning Russian. And so he attended the Russian grammar school in Plovdiv. In the mid-1960s he was accepted to study the Czech language - a university programme that only accepted 15 students from the whole of Bulgaria. In 1967 he visited Prague for the first time and was enamoured. During the holidays he worked as a guide in Sunny Beach, where he perfected his Czech thanks to Czech tourists. He experienced the dramatic August 1968 occupation of Czechoslovakia with them as well, as the tourists had difficulties returning home due to the closed borders. His Czech friends introduced him to the idea of a liberalised society, which was unthinkable in pro-Soviet Bulgaria. From 1970 he visited his friends in Czechoslovakia regularly. In 1996 he and his wife Tatiana immigrated to Prague. He worked at travel agencies and has translated over twenty Czech books into Bulgarian, including the works of Vladislav Vančura and Bohumil Hrabal.