Art is always something supremely difficult, because one more or less approaches imaginary perfection, but never attains it

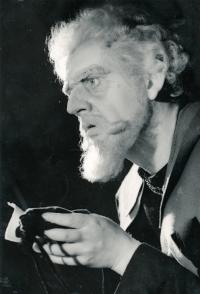

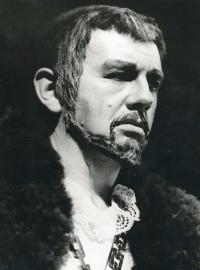

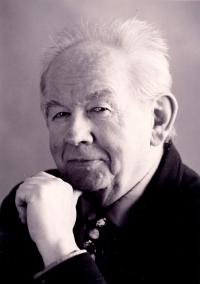

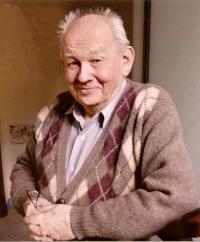

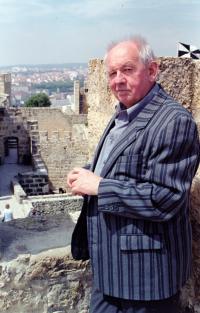

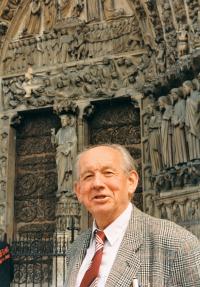

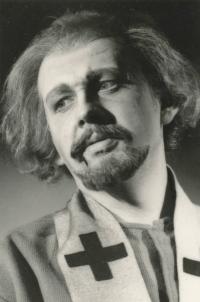

Richard Novák was born October 2, 1931 in the village Rozseč. Already when he was a young boy he was interested in music: he played the violin, organ and he also sang in a choir. After graduation from grammar school he chose a career path in the church and he joined a seminary for priests, but the institution was abolished one year later and Richard thus became completely devoted to music again. He graduated from the music conservatory in Brno and since 1954 he was active as an opera soloist in the State Theatre in Ostrava and later in the Janáček Opera in Brno. During more than sixty years of his professional career as a singer he performed in more than three thousand performances. His repertoire included complete opera works of Bedřich Smetana, Bohuslav Martinů or Leoš Janáček. As for the foreign composers, he sang compositions by Rossini, Mozart, Verdi, Prokofiev and Alban Berg. Richard also appeared as a guest singer abroad, especially in Janáček‘s operas. He frequently performed in large oratorios. He managed to achieve many accomplishments and much acclaim even despite never joining the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. For his contribution to music he has been awarded with the title Artist of Merit, the Thalia Award, the Award of Antonín Dvořák or the Award of the Ministry of Culture.