Czechoslovakia made a person of me

Stáhnout obrázek

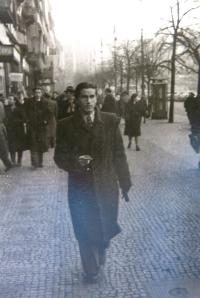

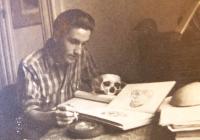

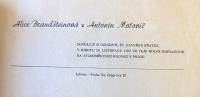

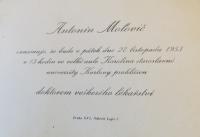

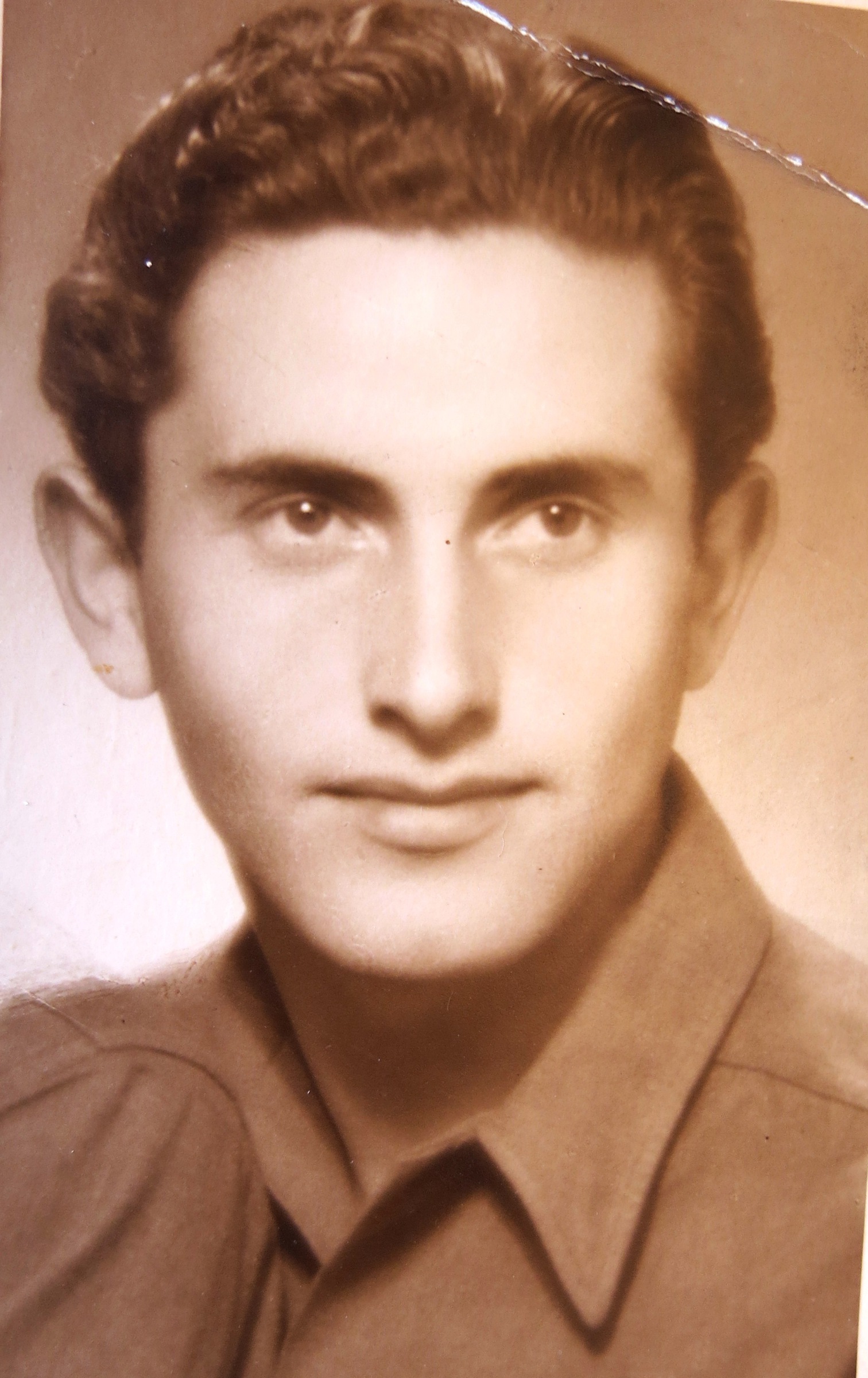

MUDr. Antonín Moťovič was born on 17 January 1927 to a Jewish family in Khust in Subcarpathian Ruthenia. He had an older brother and a younger sister, his father traded with wood and his mother tended to the house. The witness attended a Czech grammar school in Khust. In 1939 Subcarpathian Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, and his father was drafted into the Hungarian army as a manual labourer. On 15 July 1941 the mother and her three children were arrested and deported from Khust to Yasinia, which was a collection point for Jews without state citizenship. Several days later they were transported to the village of Tlustá (Tovste in Ukrainian), which was part of the occupied territory of Poland. Most Jews without state citizenship were murdered in August 1941 in mass executions by Einsatzgruppen units in Kamianets-Podilskyi. The Moťovič family managed to escape the transport to Kamianets-Podilskyi at the last moment thanks to the intervention of the mother‘s cousin, who helped them return to Khust in secret. The family was arrested a second time in summer 1944; after several days in the ghetto in Khust they were deported to Auschwitz in June 1944. The witness and his father were taken first to the Mauthausen concentration camp and then to the labour camp in Eibensee, where they dug the foundations for a road through a mountain valley. His father died in early May 1945, soon before the camp was liberated. Antonín Moťovič returned to Khust, where he was reunited with his mother, sister, and brother, who had survived the war in labour camps. When Subcarpathian Ruthenia was annexed by the Soviet Union, they decided to move to Czechoslovakia. The witness attended a grammar school in Prague and then studied medicine at university. His siblings emigrated to Israel and the USA after the war. After graduating, Antonín Moťovič worked as a surgeon at the hospital in Krč. From the 1960s he and his family applied unsuccessfully for permission to emigrate to Israel. In 1965 he and his wife and two daughters immigrated to Israel via Yugoslavia. He was employed as a surgeon there and was one of the founders of children‘s surgery in Israel. For his contributions in the field of medicine, he was awarded the Kafka Medal in 1998. Antonín Moťovič has two daughters and lives in Kfar Saba in Israel.