When he saw the call for Husák’s resignation, he nearly fainted. Still, he read the students’ demands aloud to the crowd

Stáhnout obrázek

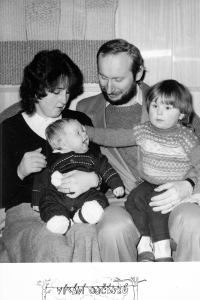

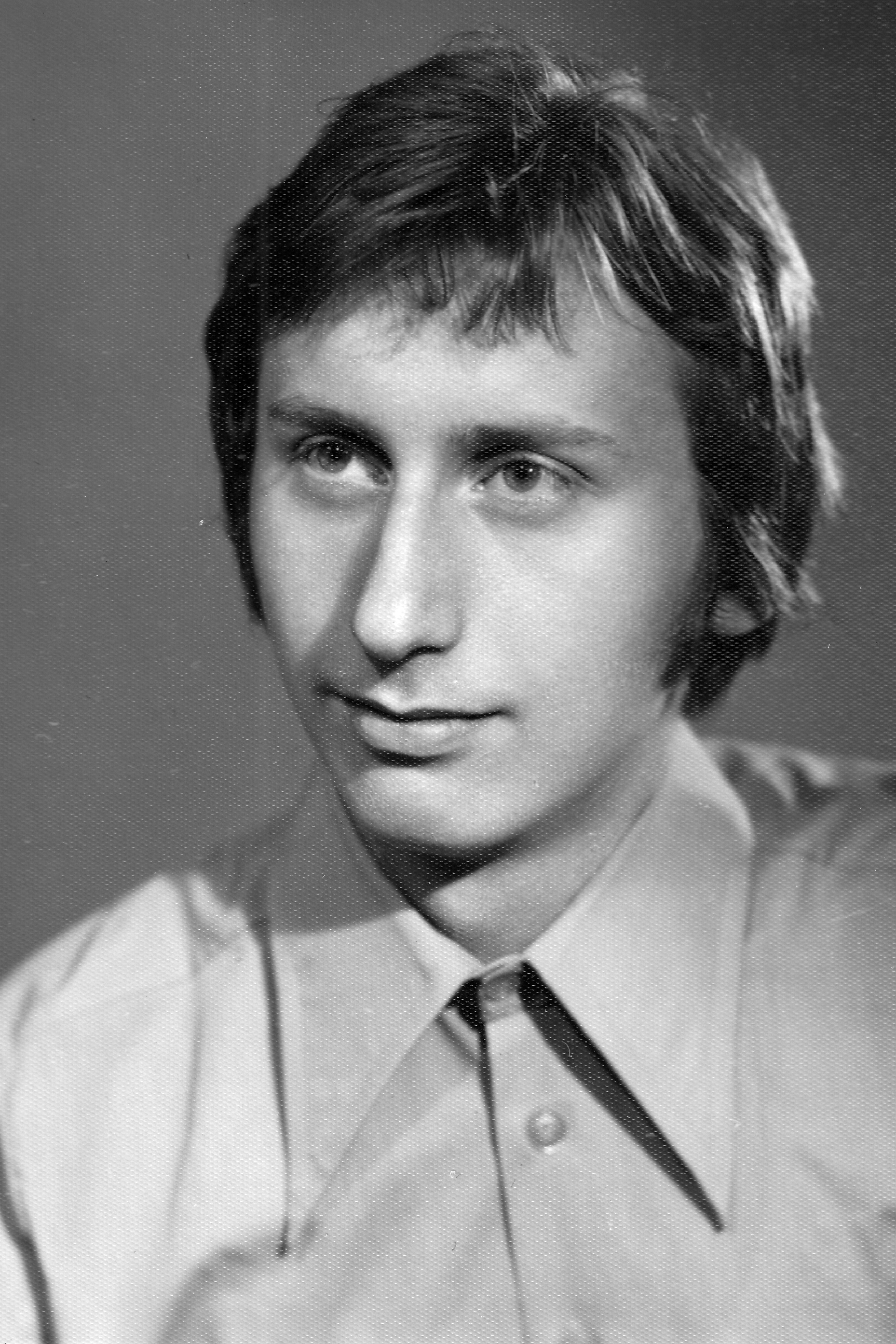

Petr Louda was born on September 16, 1958 in Jablonec nad Nisou. He comes from a mixed Czech-German family. His father was Kurt Louda (born 1931) also from a mixed Czech-German family, his mother Erika Loudová (born 1938) from a German family. Until he was four years old, he spoke only German. The children called him „Kompeta“ after his grandmother‘s call „Komm, Peter!“ He was trained as a locksmith. He took his German origin as a handicap until the war, which he served in Slovakia from 1979 to 1981. He worked for a while as a plant manager in cardboard packaging, then earned his living as a welder in JZD (Unified Agriculture cooperative) Janov nad Nisou until the Velvet Revolution. In the November days of 1989, he joined the revolution in Jablonec nad Nisou. On Sunday, November 19, he organised a demonstration in front of the Jablonec town hall the next day, following the example of Liberec. At that time, eight people gathered on the square under police supervision. He was arrested. On Wednesday, several thousand people came to the town hall. Petr Louda read out a student appeal on the square. He became a member of the Civic Forum Coordination Centre. After the revolution, he went into business as a merchant. He married Dagmar Treglová. They raised two sons. In 2009 he joined TOP O9. In 2024 he lived in Jablonec nad Nisou.