Lidi vykřikovali protikomunistický hesla a my jsme jim k tomu hráli

Stáhnout obrázek

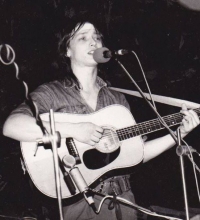

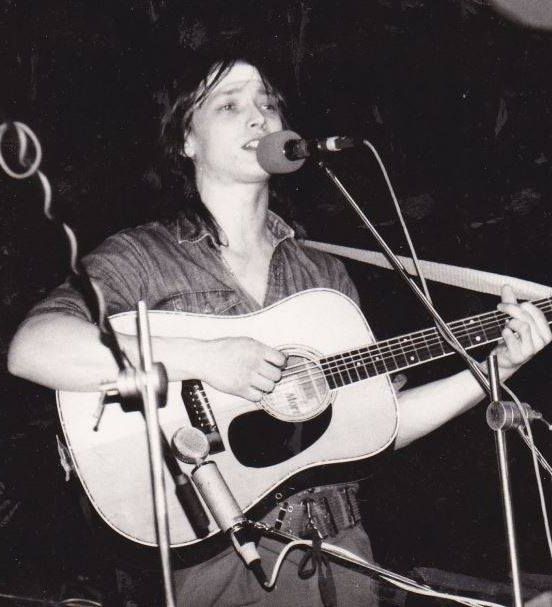

Miroslav Leicht was born on the 2nd of April in 1962 to an anti-Communist family. The property of his wealthy grandmother, Jenny Leicht, was misappropriated by the Communists and she had to pack ice cream in a dairy factory. Miroslav’s father, Alois Leicht, signed the Two Thousand Words manifesto in 1968, for which he was demoted to a lower position in the Škoda factory where he had been working. When stilll at school, Miroslav and his older schoolmates started a successful bluegrass band called Jezdci [Horse Riders]. In 1978, he became the youngest member of the newly founded bluegrass band, Cop [Braid], which won the Green Porta award at the Porta music festival in 1979. In the same year, Miroslav was taken away right from the school to be interrogated by the State Security. In 1983, several band members emigrated, mainly to the U. S. and to Canada. Miroslav had been interested in big beat even before so he joined the Galerie band in which he has been playing since. In 1986, he revived the Cop band. Until 1987, he worked as a driver, then he got a job as a stage technician in the cultural centre of the Revolutionary Unions Movement (Revoluční odborové hnutí, ROH); there he encountered many people with similar views. In summer 1989, at the Porta festival which took place in Plzeň that year, he signed the Several Sentences manifesto. During the revolutionary days of November 1989, owing to his job in the cultural centre, he provided props, sound systems and support service for the demonstrations in the streets of Plzeň. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, he became a professional musician, he performed with the Cop band, often even abroad. In 2001, they got the Anděl music award. At present, Miroslav keeps performing, organises festivals and has his own show on the Samson radio station.