Radio - those are words straight to one‘s soul

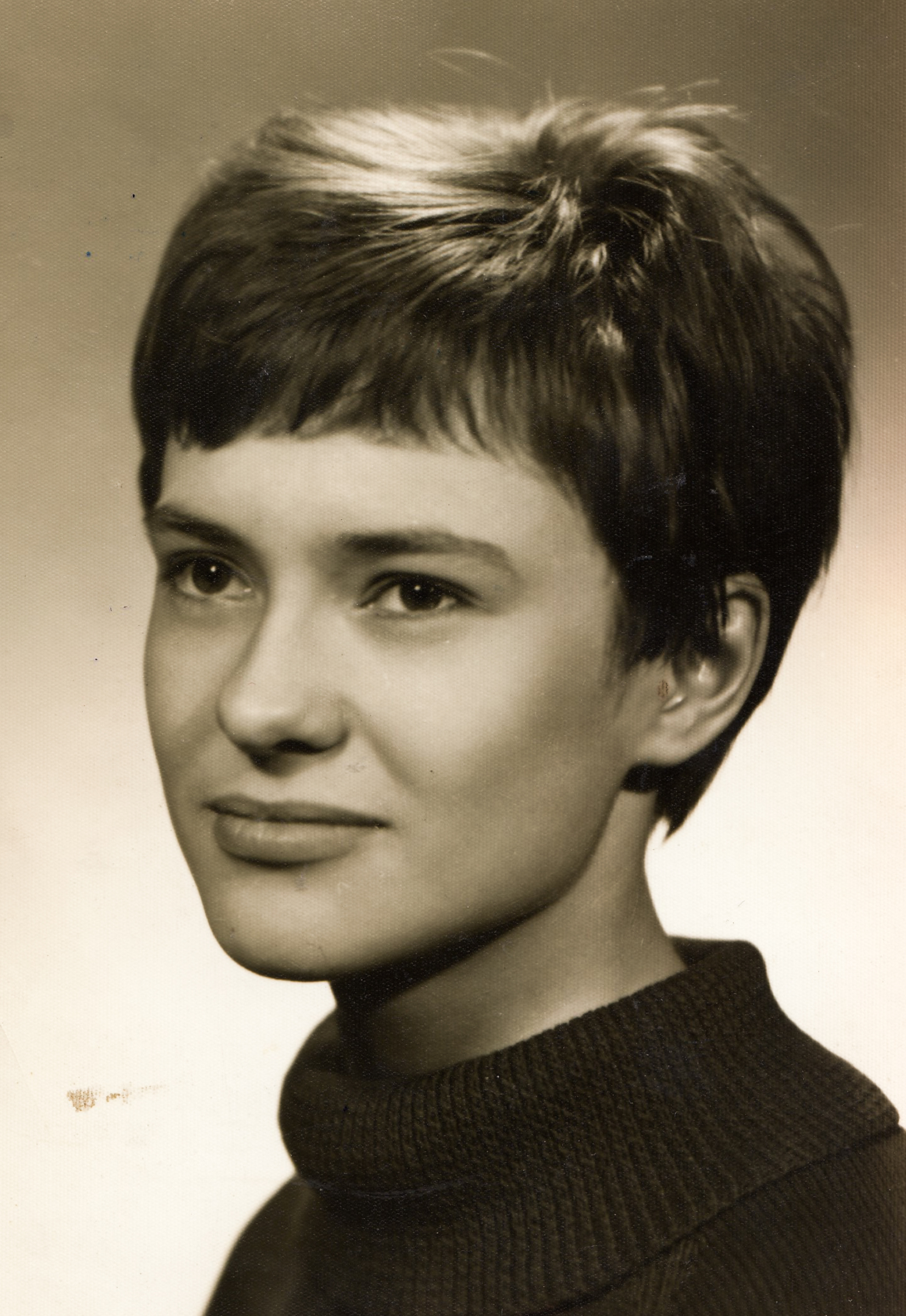

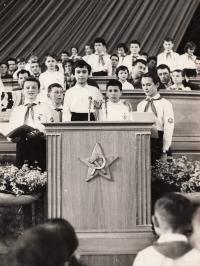

Hana Kofránková was born on 5 January 1949 in Prague into the family of a bank employee and a housewife. As a child she was often sick due to a heart disease and had spent practically all of her first grade at a hospital. Also thanks to the fact that as a child she was often at home or in medical facilities she grew fond of radio broadcasting. She was mostly interested in radio drama for children and youth. Ever since early 1960s she competed in recitation and in mid-60s she along with Michal Pavlata starred in a new radio series Songs for Peter and Lucy. After concluding university studies at the Theatre Faculty and the Faculty of Philosophy in mid-70s she became a director of the Czechoslovak Radio. Her brother-in-law was Ladislav Hejdánek who co-sponsored the Charter 77. In the end she herself was spared persecution by the regime likely also because she signed the so-called Anti-charter which she later regretted. To the contrary, at the late-80s she signed several anti-regime petitions including Several Sentences (Několik vět) and also took active part in the Velvet Revolution at the Radio. In her work she then focused on the persona of Přemysl Pitter. Along with friends she keeps organizing author readings. On the margins she pursued documentary cinema and theater directing. She is one of the remaining legends of the Czechoslovak Radio‘s analogue era.