The fact that the town of Maříž functions is, for the most part, thanks to my father, and then also thanks to me. After 1970 Maříž was targeted for extinction

Stáhnout obrázek

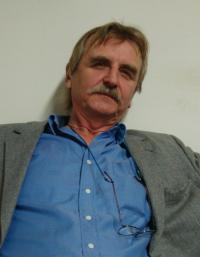

František Dušek was born in 1955 in the small border village of Maříž near Slavonice, into the family of a Border Guard. Although his family moved frequently and Frantisek studied and worked in various locations throughout the world, he visited Maříž frequently. After completing primary school in Slavonice, he trained to be a mechanic, fulfilled his military service, and got married. The promise of free housing made him decide to become a professional soldier. He began studying at boarding school, and as he received top grades, he was allowed to continue to university without having to pass an entrance exam. After graduating he was employed at the Office of the Chief Border Commissioner, where he was responsible for solving issues related to safety and security on the state border with Austria. Apart from that he also completed a postgraduate programme for diplomatic protocol in Moscow. Together with his father he succeeded in at least partially saving the village of Maříž, which was located in the border zone and was designated for a “dying out” of its inhabitants.