Once a refugee, always a refugee

Stáhnout obrázek

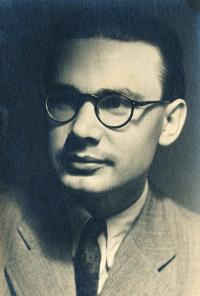

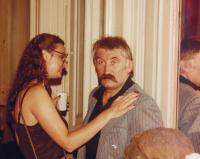

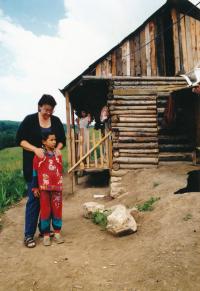

Zuzana Brejcha was born on 8 August 1953 in Prague into the family of Vlasta and Bohumil Brejcha. Her father worked as a script editor in the Barrandov film studios. In 1956, he was forced to hand his notice due to political reasons. He then worked as freelance script writer, collaborating closely with Jiří Trnka up until 1968. The same year, Zuzana was admitted to a grammar school after which she intended to study film science. However, the August 1968 Soviet invasion in the course of which their apartment was riddled by bullets, forced the family to emigrate. In October that year, they left for Vienna where they were granted asylum. Zuzana‘s father found employment as manager in the company of his Austrian friend, and he never since returned to making films. Zuzana graduated from a Viennese high school and in 1982 graduated from a film university in screenplay and film editing. From the very beginning, she was in touch with the Czech community living in the city. She had attended the Sokol sports club and her father was a founding member of a cultural club gathering Czechs and Slovaks. In 1982, she visited Prague for the first time in fourteen years, which initiated a search for her lost identity. For a year and a half, she had been dating the actor Pavel Landovský who introduced her to people from the Czech underground living in Vienna. In 1983, she met Václav Havel in Prague, which made her a person of interest to the secret police. She had spent the November 1989 events in Prague but never returned to Czechia permanently. She worked as a freelance film editor and she makes documentaries on Roma-related topics.