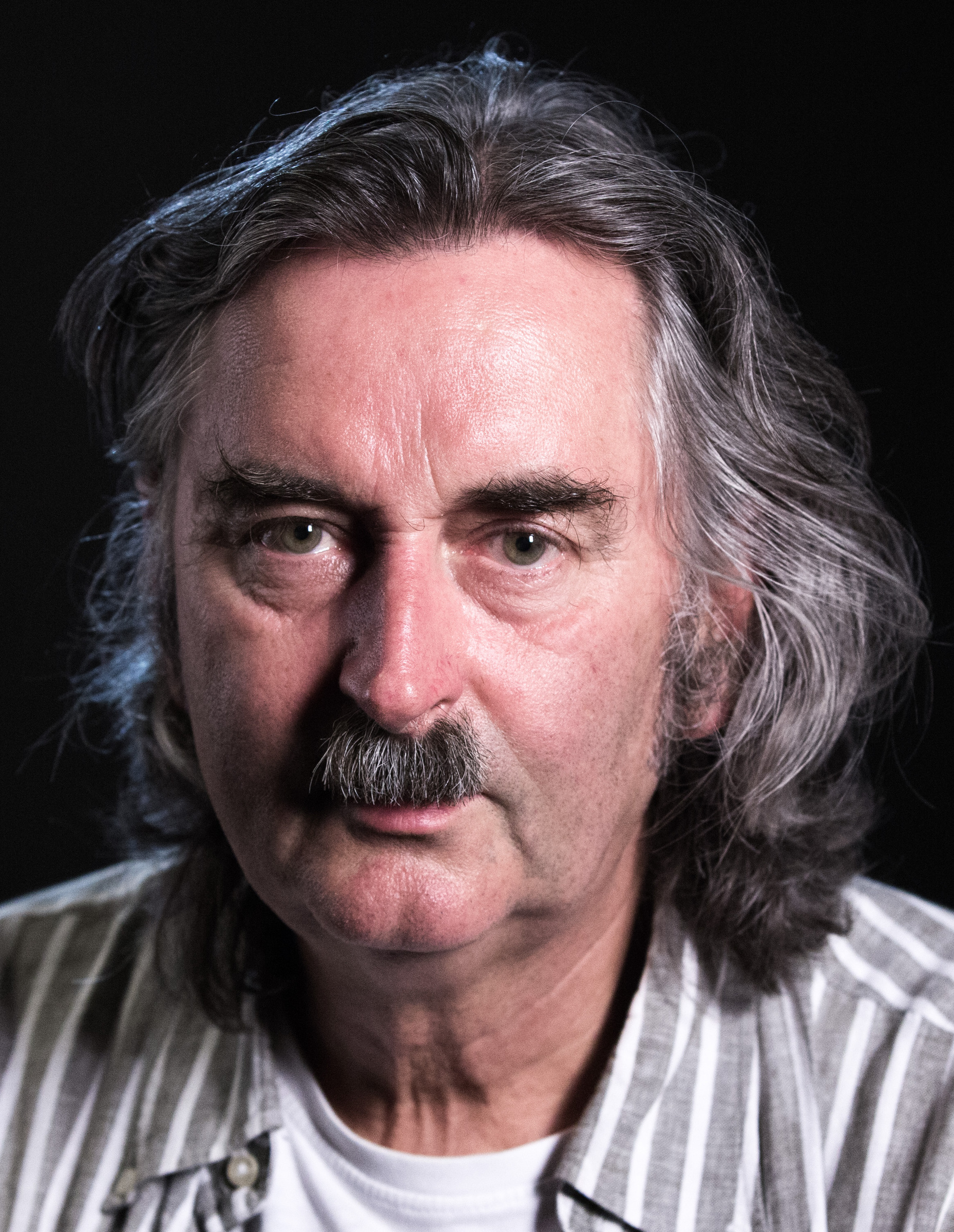

I never asked what I could or could not do

Stáhnout obrázek

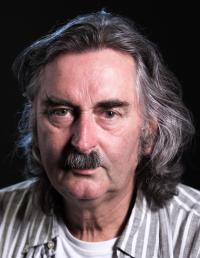

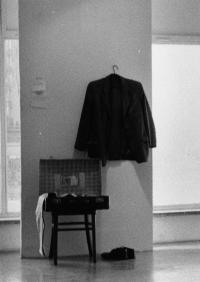

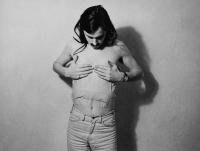

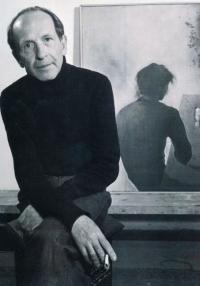

Jan Mlčoch was born on 26 February 1953 in Prague. He grew up in Podolí in the family of his grandfather, the legionary Josef Mlčoch, who was also an art collector. This experience formed him. Although he graduated from a secondary technical school, he ended up getting a job at the depository of the National Gallery. In 1974 he took an interest in conceptual art, which meant organising various events that were considered provocation under the totalitarian rule. In 1978 he changed his job to work as an archivist at Odeon, a publishing house. His friends included a number of people from the sphere of unofficial art and the dissent. He never joined the ranks of the so-called official artists, who cooperated with the regime. He was not allowed to travel abroad, and he was interrogated by State Security. He became a respected theoretician of artistic photography and the curator of the photographic collections of the Museum of Industry and Art in Prague. In 2005 he received the Czech Photography Personality Award for organising the exhibition Czech Photography of the Twentieth Century.