The aim was to punish the middle class

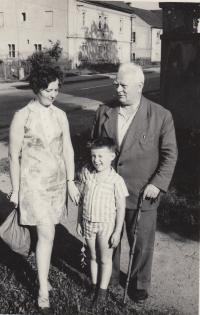

Jana Fialková was born February 12, 1942. Her father Ladislav Čechura was the breadwinner for the family. He ran a small transport company and the business prospered thanks to his effort and hard work. On June 1, 1953, Jana‘s father attended the meeting on the Republic Square, which later became known as the Pilsen Uprising. He was arrested for opposing a member of the People‘s Militia and sentenced to six years of imprisonment. He was released three years later, but he was never granted rehabilitation. The family‘s property was confiscated and they were forcibly evicted from Pilsen. After the father‘s return from prison they settled in Kyselka near Karlovy Vary and later in Františkovy Lázně. Although Jana repeatedly took entrance exams to the university and she successfully passed, she was never admitted to study. Eventually she completed evening classes of a secondary technical school which she studied while working. She worked in the company Lesoprojekce, later in an office, for the Military Construction Company and in commercial business. She is now retired and for already fifteen years she has been taking classes of the University of the Third Age.