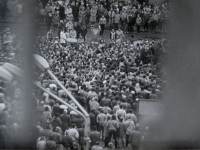

The normalisation regime was evil. It destroyed the soul

Stáhnout obrázek

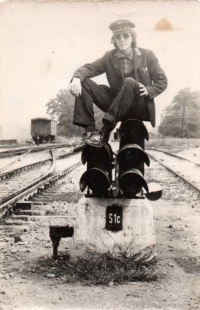

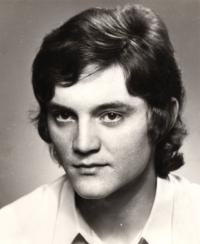

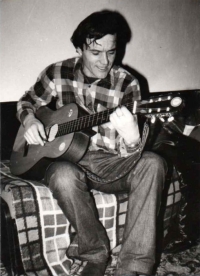

Pavel Záleský was born on 28 February 1955 into a Catholic family in Mutěnice, South Moravia. His father Petr Záleský and uncle František were convicted of anti-state activities. They served their sentence in the uranium mines in the Příbram region. The communists confiscated the family‘s fields, vineyards and other property. He graduated from the railway industrial and transport secondary school in Hodonín. At the end of the 1970s, he began to copy and distribute illegal religious literature. In the 1980s he cooperated in the production and distribution of samizdat literature with Stanislav Devátý, Jaroslav Němec and also with Augustin Navrátil. From 1985 until 1989 he was followed, harassed, detained and interrogated by the State Secret Police. In 1985 he participated in pilgrimage to Velehrad, which turned into a mass anti-regime demonstration. He signed the Charter 77 and the petition for religious freedom by Augustin Navrátil, which he further distributed. In November 1989, he was one of the leading figures of the Velvet Revolution in the Zlín region. In the 1990s he managed the Charity in Otrokovice. Later he worked as a district secretary of the KDU-ČSL (Christian Democratic Party). In the noughties he was the administrator of the pastoral house Velehrad in northern Italy. In 2021 he lived in Otrokovice.