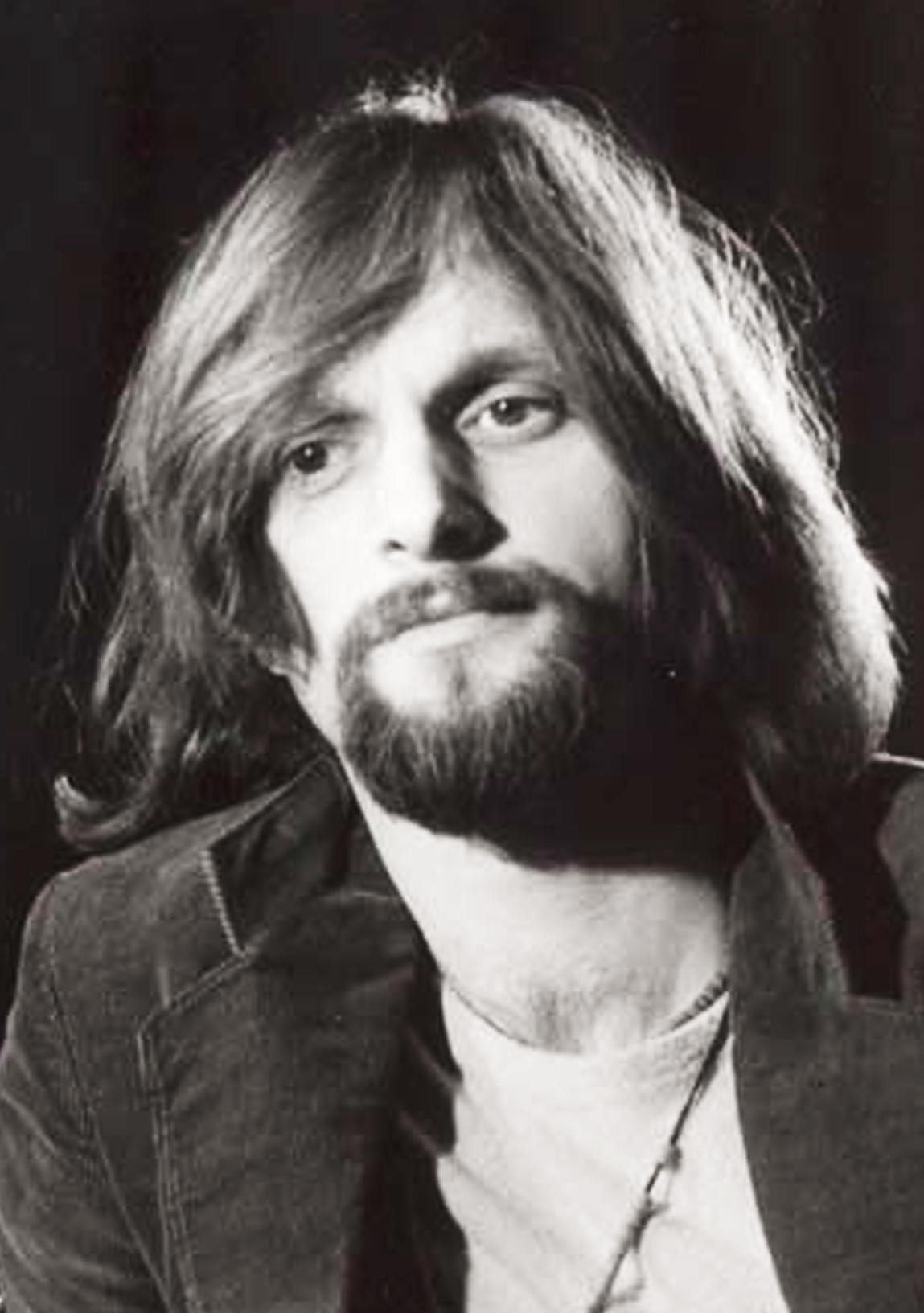

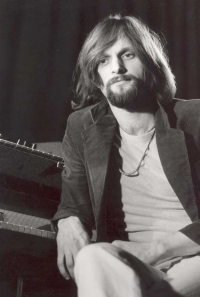

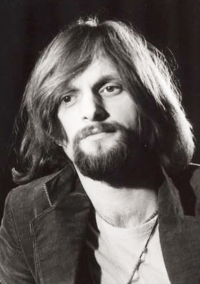

I allegedly looked like Jesus on the record sleeve

Stáhnout obrázek

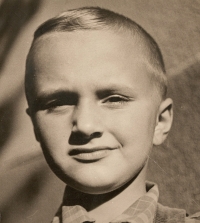

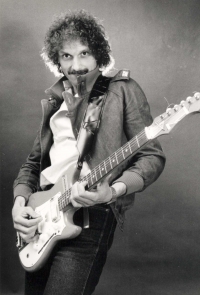

Václav Vašák was born on the 30th of December in 1949, until he was 18, he had lived with his parents and sister in Hostomice at the foot of Brdy Mountains. His father Václav was a pharmacist, hs mother Eliška was a lab technician. The Vašák family went to church regularly whichw as the probable reason why Václav did not get his credential from the primary school and couldn’t go to high school with a graduation exam. At the last moment, he was accepted to the Secondary Technical School of Electrical Engineering in Hořovice. In 1968, he started working in the Tesla Karlín factory. He recalls the street protests during the August invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies and his disgust with the pro-Soviet politics. In the autumn, he was conscripted. He spent his first year of service in the military academy in Nové Mesto nad Váhom, his second year of service he spent in Beroun. When in the army, he devoted a lot of effort to music, he played guitar and sang. In 1970, he joined a Prague rock band, Beatus, at the same time, he worked as a draughtsman. Around 1977, the whole band applied for the Army Arts‘ Ensemble but they picked only Václav and the guitar player. Václav spent two years in the folk group of the Army Arts‘ Ensemble. He studied singing and composition at the People’s Conservatory (today’s Jaroslav Ježek School of Music). In the course of the 1980’s, he played in the Václav Hybš Orcherstra or with the Zip band. At the beginning of the 1980’s, he got into trouble because of a record on whose sleeve his portrait with longish hair and full beard appeared. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia allegedly considered it provocation. His songs disappeared from themedia. Between 1985-1995 he performed as a singer with Karel Šíp and Jaroslav Uhlíř or with Ringo Čech, among others. He was a successful composer as well. In the 1990’s he started writing for various magazines, published several books and composed scores for four independent American films.

![Poster for Karel Šíp's show Letí šíp na Hanou [Arrow flies over the Haná flatland]. (From the left: Vávra, Vašák, Roth, Sodoma, Šíp) 1992

(Note: Karel Šíp enjoyed masterful puns so the name of the show is likely a pun on his surname: šíp = arrow)](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-09/Plak%C3%A1t%20k%20po%C5%99adu%20Karla%20%C5%A0%C3%ADpa%20se%20zp%C4%9Bv%C3%A1ky%20Let%C3%AD%20%C5%A0%C3%ADp%20na%20Hanou%20%281992%29%28V.V%C3%A1vra%2CV.Va%C5%A1%C3%A1k%2C%20P.Roth%2C%20V.Sodoma%2C%20K.%C5%A0%C3%ADp%29%20foto%20Antalovsk%C3%BD.jpg?itok=SYyReT2W)

![Show Branky, brepty, sekundy [Goals, gaffes, seconds; wordplay on a name of TV sports news segment called Goals, points, seconds] where Václav Vašák performed with Luděk Brábník. 1984](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-10/2_7.jpg?itok=X8SmVxGH)

![Ondřej Vetchý introduces Václav Vašák's first book, Jó, to tenkrát... [Well, those were the days...]. 1995](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-10/8_6.jpg?itok=EFpdODLn)

![Interviewing [historian] Zdeněk Mahler in his home. 2000](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-10/16.jpg?itok=Xu6j_cH5)

![Playing with Amfora [celebrities' football team] in the Slavia sports club stadium. Václav Vašák, centre, with a raised leg, wearing a headband. 1984](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-10/17.jpg?itok=0DM3BnFY)

![Václav Vašák, Lucie Bílá and Jiří Sýkora performing in the show Inventura [Inventory]. End of 1980's](https://www.pametnaroda.cz/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-10/19.jpg?itok=8s_sLNjS)