We jumped over the stream and screamed like monkeys

Stáhnout obrázek

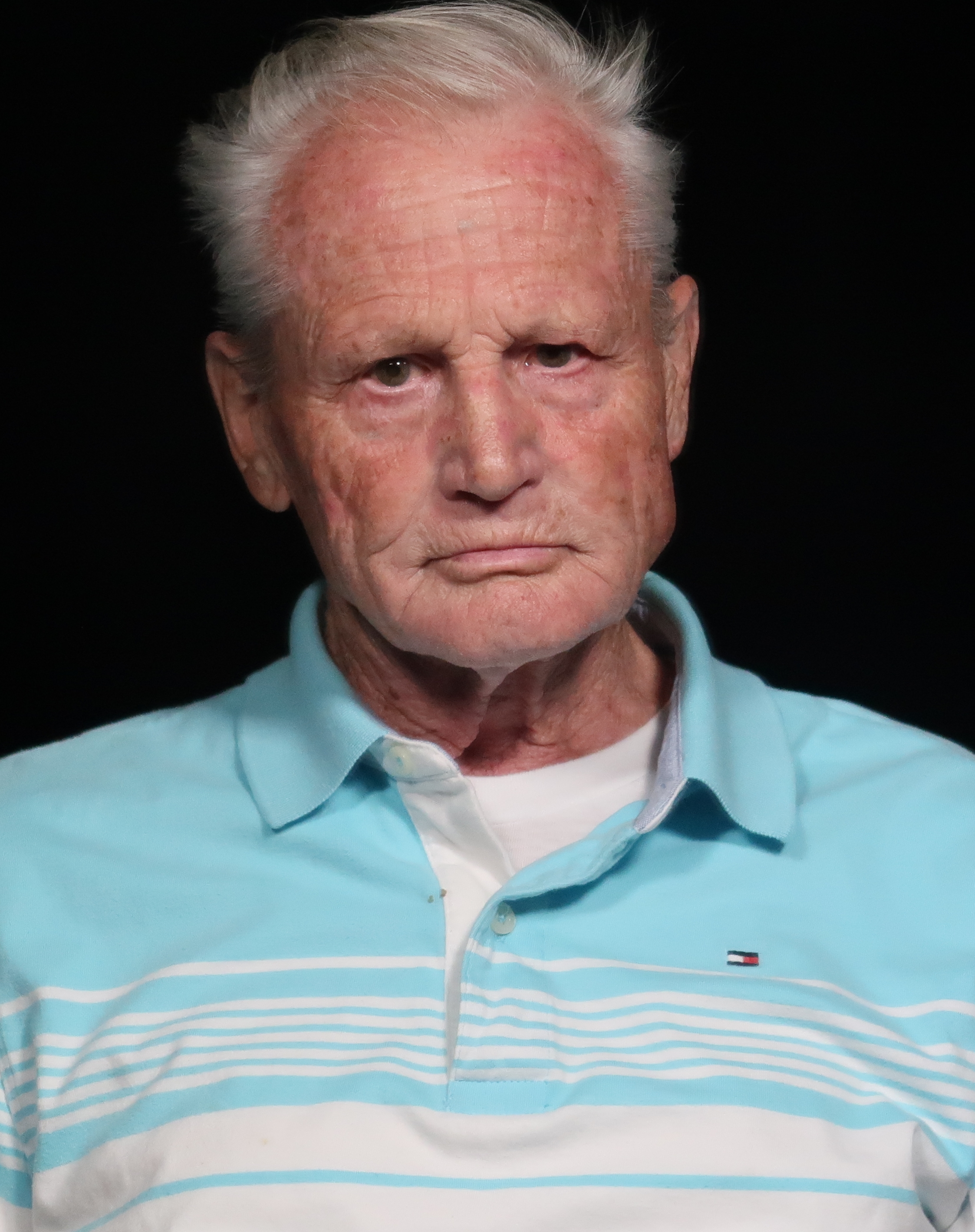

Ervín Reisky was born on 28 June 1931 in Hlučín to a mother from Heroltovice near Libavá and a master locksmith originally from Hlučín. His father declared his Czech nationality in 1924, his mother spoke German. At first he attended a Czech school, but after the annexation of Hlučín to the Third Reich, the teaching changed to German. His father was called up for service in the Wehrmacht. In the autumn of 1940 he suffered a gunshot wound in Holland, where he also died. Ervín Reisky lived in a boarding house for two years because his mother could not support him and his brother, three years younger, on his pension. After the Second World War, he finished municipal school and entered a mining apprenticeship. He earned a good living in the mine and supported his mother and brother. After the communist coup in 1948, he wanted to study, but because he was not in the communist party or the youth union, he did not get a recommendation. With three friends, he decided to leave his homeland illegally before he started his basic military service. At the end of August 1951, they left by train for Děčín and crossed the border on foot into East Germany near Bad Schandau. Wearing their best clothes, they set off without money or a map. They travelled on foot and by train through Pirna and Chemnitz to Reichenbach, where the family of Karel Staš‘ cousin provided them with food and instructions for their onward journey. In the village of Lichtenberg near Hof, they crossed the guarded border at night and checked in at a police station in West Germany. They spent some time in the Valka-Lager refugee camp near Nuremberg. Then Ervín Reisky and Karl Staš were offered a job by a Czech working for the American intelligence service. In the French zone near Lake Constance, they were trained and given pistols. The two friends returned from the border by the same route through East Germany to Czechoslovakia and Hlučín. A very risky venture for which the death penalty was imminent, they were lucky to make it. They contacted several people in Hlučín and found a possible telegraph operator. After returning to Germany, they received no further instructions and could not return to the camp anymore. Ervín Reisky found work in the mines in Essen. After four years in Germany, he was allowed to travel to Canada, where from 1955 he supported himself by running a business in various fields. He married and had two sons. His younger brother joined him after the Warsaw Pact armies invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968. They were also visited by their mother, who had in the meantime legally emigrated to Germany to join her sister. In 2019, Ervín Reisky was living in Toronto.