Emigrating and radically changing your place of life is no small thing

Stáhnout obrázek

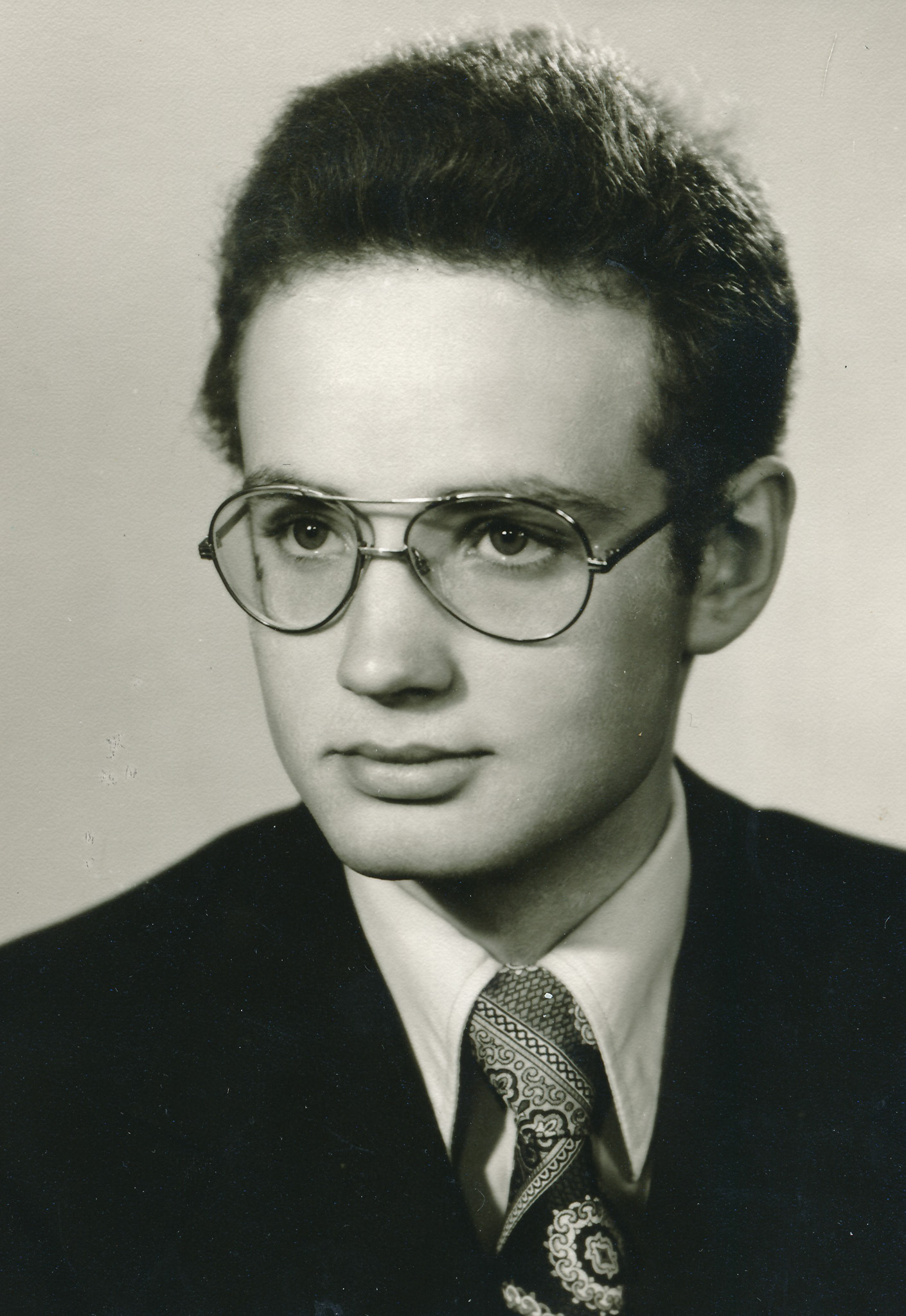

Petr Novák was born on 2 November 1960 in Štvanice, Prague, into the family of Marie and Miroslav Novák. He spent his childhood and adolescence in Prague‘s Holešovice, where he lived with his parents and brother Jan. He also spent a lot of time in the Moravian town of Kyjov with his grandmother, Ludmila Svozilová. He grew up spiritually in the Catholic community around the churches of St. Anthony of Padua and St. Clement, where his spiritual development was influenced especially in the 1960s and 1970s by Father František Kohlíček, a political prisoner of the 1950s. In addition, he attended the drama club of the actress Jiřina Steimarová, thanks to which he played in several film and television children‘s roles. In 1980, he entered FAMU, majoring in film and television production, which he graduated from in 1987 with a two-year break. He then joined Krátký film Praha, and in 1987 married Ludmila (née Muroňová), with whom he raised two sons, Vojtěch and Ondřej. After the revolution, he learned that he was being monitored by State Security for his student and Catholic activities. In 1991, he joined the state services, specifically the newly established Department for Refugees of the Ministry of the Interior. During his nearly thirty-five years of service (part of which as deputy director of the department), he was present at the birth and life of Czech asylum and migration policy, witnessed the influx of displaced persons from the former Yugoslavia, Chechnya and, most recently, Ukraine, and was involved in resettlement programmes and the Medevac programme. He lives in Břevnov, Prague.