They wanted to evict us. They interrogated my father and forced him to establish a cooperative farm

Stáhnout obrázek

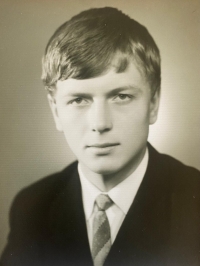

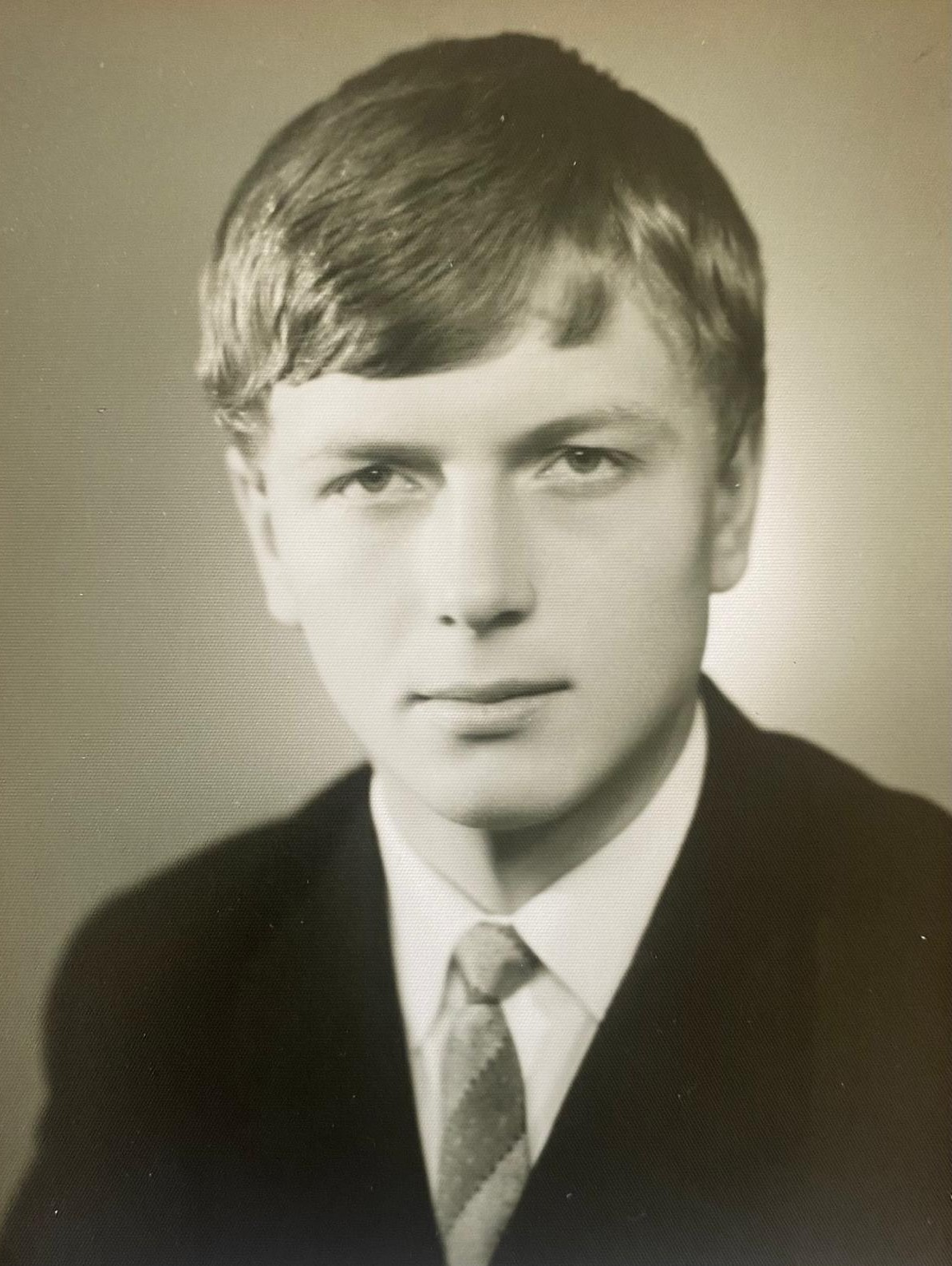

Josef Chroust was born on 24 June 1950 in Nové Město na Moravě into a family of landowners. His parents owned 45 hectares of fields, meadows and forests around Jimramovské Pavlovice. The communists confiscated part of the family‘s property and tried to evict them several times. Jan Chroust‘s father was interrogated several times in the 1950s. In 1957 he was forced to establish a cooperative farm (JZD), which ironically enjoyed great success and received the Red Standard for its achievements. Josef Chroust completed primary school in Jimramov and in 1965 he began studying in Ivančice in the field of agricultural mechanisation. He graduated in 1969 and continued his studies at the University of Agriculture in Brno. After themilitary service, which he completed in Louny, he returned to his native Vysočina and worked for years as a mechanic in various villages in the Žďár region. He married the daughter of an evangelical pastor Josef Batelka and they had three children. At the end of the 1980s, he began working in a inen workshop as an instructor, and thanks to this occupation, after the Velvet Revolution, he made several trips to South Carolina for work. After the fall of the regime, all of his family‘s property was returned to his family, and his brother began farming privately. Josef Chroust was living in Bobrová in 2024.