Years of uncetainty what next minute will bring

Stáhnout obrázek

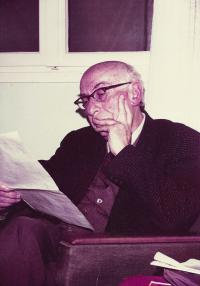

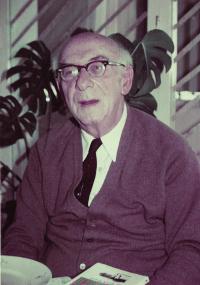

Albert Avraham, now Avri Fischer, was born in Vienna in 1935 and grew up in Bratislava. His father Desider David Fischer worked as a baby doctor and the consultant at the Jewish hospital in Bratislava. His mother was named Lilly, née Perl. His uncle Gusta Fischer became one of the very first victims of Slovak anti-semite sentiments. He was attacked in the street by a group of thugs, suffered serious head injuries to which he later succumbed. His father’s sister was a well-known leader of the local Jewry. Around 1940 the Fischers had to leave their luxurious flat in today’s Hviezdoslav Square. The moved to a villa on the Bratislava hill. Avri attended the neolog Jewish school but after the second year the school was closed. Most of the children and teachers were taken to transports. A Jewish boy was not allowed to transfer to the state school. Out of the initiative of his parents, he attended classes in the family of engineer Krasňanský. His father’s profession protected them from the transport. Same as many other Jewish professionals, indispensable for the Slovak State, he received a certificate of being excluded from transports. This held until September 1944 when they had to go into hiding. His parents survived to the end of the war in a refuge built in the warehouse on their neighbours’ garden. Avril spent the day with one family, the night with other. One night, however, there was a Gestapo raid. The boy escaped only thanks to his Aryan look and false document. He then changed his place of refuge. Immediately after the war Albert joined the youth Zionist movement, determined to leave for Israel just after his school-leaving exam. Everything was sped by the communist coup. He left in 1949 with the consent of his parents and found his new home in the Kfar Masaryk kibbutz. He got married after completing his military service in 1955. He worked as a teacher in leading positions of the Kibbutz movement.